Alan Semerdjian and Aram Bajakian

Alan Semerdjian and Aram Bajakian

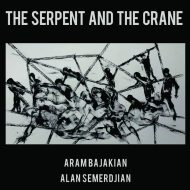

The Serpent and the Crane (Spoken word with music)

Funded by an Armenian General Benevolent Union Performing Arts Grant and a Creative Armenia Spark Grant

Reviewer: George Wallace

If collaborative performance is a horserace, then Alan Semerdjian goes trifecta with his ambitious new project The Serpent and the Crane, a winning confluence of music, poetry, and ethnically oriented social consciousness in the form of a spoken word album.

Semerdian, grandson of famed Armenian-American painter Simon Samsonian (who rose to fame in the Armenian Diaspora in Cairo, Egypt in the 1950s and 60s before settling in Queens, NY) pairs with Vancouver-based guitarist Aram Bajakian, also the grandson of a Genocide survivor and a prodigious stylist who has performed with the likes of Lou Reed, John Zorn, Malcolm Mooney, and Diana Krall.

The result is a twelve-track album that features poems by Semerdjian – as well as Armenian authors Peter Balakian, Diana Der-Hovanessian, Siamanto, and Daniel Varouja – set to music by Bajakian.

Bajakian and Semerdjian have a record of commitment to their respective crafts that matches their commitment to their cause. Bajakian has been called “a virtuosic jack of all trades” by the Village Voice. Semerdjian, who is as well known for his travels on the alternative music circuit as for his poetry, has earned high praise for his poetry by Pulitzer poet Peter Balakian.

Still, striking an effective balance between poetry, music, and rhetoric is no simple matter, and the substantial success on the part of these two talented fellows in doing so is a creditable feat.

Semerdjian offers several poems and lyrics that display a consummate craft, accurate both in a forensic sense and in terms of emotional tension, volatility, and restraint. Take “Grandchildren of Genocide,” the opening cut, which sets the emotional stage for what is to follow in the entire CD. “When we think of genocide we think of bomb-fields and gas chambers,” writes Semerdjian, “we don’t think of young democratic people and pomegranates. / We don’t think of young democratic people with pomegranates / at bazaars.”

In “Figures of Armen,” “children made of dust sing songs in the wind.”

A sense of collective resilience is communicated effectively in “Like A Sad Monster”:

Like a sad monster in search of grief,

like the weathered ruins of pagan temples,

like the body on fire without fire,

a million screaming numbers without their charts …

… we continue to believe what is unbelievable,

continue to do what is unthinkable.

Other poems are deftly selected by Semerdjian for interpretation. One of the most successful among them is “History of Armenia,” in which Peter Balakian imagines his grandmother coming to him in a dream, conflating the trauma of the early century with a similar though more contemporary desolation in New Jersey:

West Orange was burning

Montclair was burning

Bloomfield and Newark

were gone.

Then there’s the disturbingly graphic witness offered up in Siamanto’s “The Dance.”

With a torch, they set

the naked brides on fire.

And the charred bodies rolled

and tumbled to their deaths …

Throughout, Bajakian’s instrumental support provides a raga-like foundation for the words, sometimes akin to a drone but always attuned to the message and tone of the particular poem. His music is tantalizingly exotic and yet welcoming to the listener; in effect, offering up a broad fusion of jazz and new age electronica, sometimes meditative, other times hypnotically evoking the souk or dervish.

Semerdjian and Bajakian are deeply attuned to the trauma of their shared heritage. “We did our research,” says Semerdjian. “We looked at a few spoken word collaborations and realized we didn’t like it when it seemed the music just tended to support the words. That’s why we sought to make it so that both instruments worked in conjunction as a duo, rather than soloist with accompaniment.”

Ultimately, The Serpent and the Crane sets the stage for a new view into a troubled chapter in twentieth-century history that – three generations on – still reverberates through the lives of many Armenian-Americans today.

For the rest of us, the story of the genocide and dislocation experienced by Armenians a century ago is perhaps less likely to have been incorporated into our socio-historical awareness. The atrocities of that era have in many cases been consigned to the status of a footnote to world history.

If not for the willow-like persistence of third-generation Armenian-American artists such as Semerdjian and Bajakian, who dredge and re-dredge their family and community heritage, that story might lose all currency. Hence, beyond the undeniable aesthetic values, this project presents a kind of moral imperative for listeners to pay attention to the poetry and music of a people thus maligned.

That alone makes this finely crafted spoken word album a “must listen” – if only that it reminds us how the profound experiences of former times resonate in the music and poetry of Armenian-American artists a century since they transpired.