Alexis V. Jackson

Alexis V. Jackson

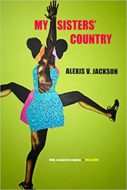

My Sisters’ Country

Kore Press

Reviewer: Brian Fanelli

Alexis V. Jackson’s collection, My Sisters’ Country, is a book with impressive historical scope—integrating numerous influences and references, and underscoring everyone from Gwendolyn Brooks to June Jordan to the four Black Girls, Addie Mae Collins, Carol Denise McNair, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley, who were murdered in the 16th St. Baptist Church Bombing of 1963. But there are plenty of contemporary shout-outs here, too, including song and lyric mashups that namedrop Cardi B and Beyonce, among others. Initially, the references can seem overwhelming, but collectively, they create a fine-tuned collection that primarily explores a Black woman’s identity.

Along with historical and pop culture influences, My Sisters’ Country is also a book that reckons with religion and the conflict the speaker feels towards Christianity and how it othered her. This feeling is especially palpable in “Dear Mom,” which looks and reads like a letter on the page. It opens, “You wanted me when God didn’t. Told me to love Him anyways.” I am especially struck by those two opening lines. On one hand, it shows a mother’s love towards her daughter, while on the other, it shows the speaker’s very complicated and often ugly relationship with religion, how it made her feel ashamed and different. It’s also interesting how God is later struck out in the poem’s lines and replaced with the pronoun “He.” Perhaps the speaker is reclaiming her notion of God here and challenging the idea that God needs to be a male, patriarchal, often white figure. The poem is also a plea from the daughter to better understand her identity and this relationship with religion, including the sin she feels but doesn’t understand. This opener is important as it sets up many of the ideas and themes with which much of the book wrestles, specifically a complicated identity, a conflicted sense of self, and a personal history involving family, religion, and Blackness.

In “Blue-Brown” some of the ideas expressed in “Dear Mom” are reiterated, but it’s a different time and location. This poem focuses on the speaker and her niece, who also struggles with understanding her sense of self, specifically in terms of color. It opens:

My niece runs her hand across

the top of my car.

She calls it maybe black—

says it might be navy—

but she can’t tell in the dark.

She is 7.

She grabs her titled afro puff

and asks me what color it is. I say brown.

She says I’m right, but

some of the kids in her class

think it’s black.

She says she tells them

it’s brown.

She says her ballies are blue—

true blue, she says—the blue

you can see at night time.

This exploration of color continues throughout the remaining stanzas, as the niece labels herself and the speaker/her aunt Black, but not black like the speaker’s car or the street. The niece adds, “We’re the Black that’s really brown, like / her mommy says her puff is, like / the floor in her new house is, like / my eyes, not / maybe brown – like / some cars are really navy—but in the dark/ and in the day / everybody else / can’t tell sometimes.” I’m floored by the niece’s voice in this poem, the distinction made between brown and Black, as well as the niece’s increasing awareness of her own identity and skin color. It also reminds me somewhat of the opening poem in terms of the voice and the coming-of-age narrative. Much of this book explores identity through various Black girls and childhood. “Blue-Brown” is certainly the case. It’s a narrative poem rich with nuance.

“Fresh Princess Sonnets,” meanwhile, takes everything about the pop-culture staple The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and turns it on its head. This is one of the book’s most jaw-dropping sequences, rich and explicit in its indictment of the American dream and ideas about prosperity and who has access to that. Many of the sequences in this longer piece are set in Philly, the poet’s hometown. The first sequence is steeped in Black girl childhood again. It also utilizes another pop culture icon, Scary Spice, to make another astute commentary. At the end of the poem, the speaker recalls playing with other Black girls, pretending to be Spice Girls, “Scept no one be Scary Spice in pretend. / Had to be her enough when we not here. / Had to be her all the time when we not.” Jackson truly uses pop-culture references masterfully, especially music, and here the Black girls would rather pretend to be Posh, the wealthy-looking white spice girl instead of the only Black Spice Girl. Those last lines haunt.

Yet, in the sequence’s second poem, the speaker praises Aunt Viv, also from Philly and with dark skin and a job as a professor. “Aunt Viv was / dark skin Philly girls winning—dark skin, skinny, Philly girls winning yo,” the speaker says. Perhaps most importantly, as the speaker notes in the closing line, Aunt Viv, “with her own shit,” was happy. It’s a great contrast to that first poem, where the Black girls didn’t want to be Scary Spice because they lived that all the time. The sequence also does a stellar job addressing microaggressions. This is especially true of the fourth poem, when the speaker recounts attending private school in the ’burbs. Her classmates thought she lived in “the hood,” while her teacher always said, she’s so “polite” and “bright.” She also had to deal with a faculty that was nearly all white, except for the one who told her and the other Black girls “not to be hoochie mamas.” Yet, it was also a school with college-prep on the website, “where it looked like more Black people were / there than true.” What’s striking about this sequence, overall, is just how well Jackson takes the fairytale story of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and rewrites it. Instead of a story about a young Black man from West Philly who moves to a swanky neighborhood to live with his wealthy Black relatives, we get the story of a Black girl reconciling with her identity, getting the chance to attend a fancy private school, while struggling to understand what that means. The sequence is funny at times, while possessing the depth and insight of much of the book’s strongest poems.

The collection has plenty of narrative twists and turns, but Jackson isn’t afraid to experiment, either. Much of the book relies on collage, clipping together song lyrics, bible verses, other poetic forms, and various lines from Jackson’s mentors to develop the rich themes that populate the body of work. Even if it’s difficult at times to find something to latch onto in some of the more highly experimental forms Jackson uses, it’s still impressive how many risks she takes, especially in the book’s later half. Overall, My Sisters’ Country is a distinct collection. Jackson’s work is bold, fierce, raw, revealing, and, ultimately, beautiful.