Allison Joseph

Allison Joseph

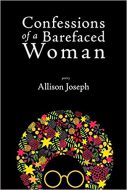

Confessions of a Barefaced Woman

Red Hen Press

Reviewer: Brian Fanelli

Reading Allison Joseph’s latest collection, Confessions of a Barefaced Woman, feels like a much-needed reprieve and act of resistance against the onslaught of negative news. The narratives spun within the pages are a celebration of literature, black history, and the quieter moments in life, like a married couple’s decision to feast on Klondike bars and plastic tubs of sherbet after feeling too tired to drive anywhere or fight anymore. By merging personal narrative with broader issues, specifically feelings of Otherness, feminism, and racial identity, Joseph constructs deft poems that resonate well beyond this era, at the same time speaking to the current moment with much-needed humor.

Most of the collection deals with the theme of identity, and the book’s opening poems specifically address the speaker’s childhood and adolescence, including her relationship with family and her love of books. In “In the Public Library,” the speaker finds solace among the shelves of damaged spines and thumbed-through paperbacks. In silence and in shadow, she discovers, “sounds discrete as bricks, jagged as shards // of bottles smashed against the library’s / concrete steps, its entrance and alley // reeking of piss, booze, its pavement / giving way, cracked along city fault lines.” The rough and tumble neighborhood is contrasted with what the speaker finds inside, specifically the power of language.

Here I learn the potency of words,

their sounds resounding in my head,

ears, equilibrium shaken,

words destined for my preteen ribcage,

my body a bony geometry. Here,

the hours teem with voices, their rhythms;

coiled tense, I lean on words and love

all this—broken bindings, smudged print,

fondled pages, my library card,

warm slip frayed in my taut grip.

It is also through books that the speaker comes to understand black history as an adolescent. In “Reading Room,” the speaker recalls how her father sold books in Toronto, “books of pride, sorrow, anger,” and such books piled up in the family living room in the Bronx, a reading room that the speaker would sneak into. It was there that the speaker first discovered Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, Malcolm X’s autobiography, Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery, and Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, among others. Like “In the Public Library,” the poem is grounded in a specific setting and a moment of awakening for the speaker, a moment when she wonders if she too could dream in words and make her voice known. At the end of the poem, she ponders,

Could I join these men if I let words

dream in me, if I struggled, didn’t

settle, my gaze as bold and forthright

as Frederick Douglass’s, Booker T.’s?

Wiping each book clean, I kept that room’s

order, my torn rag mottled, spotted,

dark with that week’s dust.

There is much to be said about the closing stanza of the poem, specifically how the speaker takes great care of the books, not only dusting them, but also understanding their importance and the weight of history that they carry. As “In the Public Library,” the books discovered in “Reading Room” contain a type of power for the speaker that makes her wonder if she too should write.

Though the father is mentioned briefly in “Reading Room,” his presence is felt more heavily in other poems, one of the starkest characters in the first half of the book, often brimming with anger and not wanting his daughter to read. In “O Holy Night,” he makes his entrance in the poem by taking a razor to the angel atop the Christmas tree, thundering about Christmas being the white man’s holiday. The poet is careful never to simplify him into a cliché, however, and a few lines later, she provides his life story that at least somewhat explains his anger at constantly being Othered. She writes,

There would be no singing today,

no hymns with “thee” and “thou,”

no praising a great white Father,

who would save us blacks from

our sinful essence, a burden

I could see every time he complained

about being called out of his name,

being made to feel less than a man.

He crossed oceans—from Grenada

to England, England to Canada—

crossed borders—Canada to the US—

all for nothing, all to be treated

like nothing. So no white angel

was going to mock him

in his own house, no matter

how much my mother tried

to pin his arms behind his back,

no matter how many angels lurked

above us, their skin pallid white,

their hair sinuous wisteria.

The poem’s slight use of repetition—especially the simple phrase “nothing”—amplifies the father’s pain and backstory. “O Holy Night” is one of many examples as to how Joseph’s poems are rooted in memory while addressing deeper issues and feelings of Otherness.

The second half of the book shifts to adulthood, as the speaker navigates a career in academia as a black woman. In “To Be Young, Not-So-Gifted, and Black,” the speaker summons the wisdom of playwright Lorraine Hansberry to deal with a complaint on a student evaluation that said, “I wouldn’t have taken this class / had I known all we were going to read / was black poetry!” Yet, the speaker states that the only black poets taught that semester were Hayden and Harper. She then wonders if it was her black face that the student hated and her lips “turning every poem into black poetry, / into what so offended him or her that poetry / was now forever spoiled?” Yet it is again through literature that the speaker finds courage to deal with such racial resentment. She imagines Hansberry speaking to the student so wittily that the student would want to be black. By the end of the poem, the speaker says, “Lorraine’s words make this burden of black / something I can handle as I add more / black names to the syllabus, more chances / for the people who will always hate my skin / to hate it even more, learn less.” She realizes that maybe some students will be turned off by the incorporation of additional black literature on the syllabus, but by the final line, she embraces and claims her identity and history.

Confessions of a Barefaced Woman contains brave poems that address self-doubt and overcoming such doubt through finding role models in library books, black authors, and Nazi-fighting superheroes, such as Wonder Woman. Joseph’s lines are lean, musical, and sometimes funny, creating a personal song that weaves family history, feminism, and racial identity into an honest and bold collection: very much the poetry that we need right now.