Beth Copeland

Beth Copeland

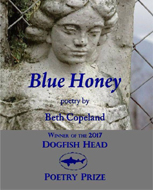

Blue Honey

The Broadkill River Press

Reviewer: Cindy Hochman

In Beth Copeland’s award-winning collection Blue Honey, the Greek goddess of memory, Mnemosyne, hovers protectively, safeguarding the poet’s own recollection as she documents her parents’ progressively dwindling recall. Told in narratives that are both straightforward and imaginative (many of them in couplet form, as if to emphasize the double whammy of having to cope with both parents’ afflictions), the poet’s tenderness is palpable, and yet she avoids lapsing into the maudlin, retaining an omnipresent and universal nostalgia while allowing herself to candidly vent her frustrations and impatience (and need to down a few Zombies); and capturing family love without glossing over the blemishes and shortcomings. For instance, in the poem “What I Remember When He Dies,” a title that presents an initial appearance of sentimentality but turns out to be anything but, Copeland relives one of the less delicate moments: “He yanked // my ankles, held me / upside-down and slapped // me like a midwife / forces a newborn baby // to breathe….” It is this willingness to reckon with the rough patches that makes these poems especially trenchant, navigating through the often heavy-handed and heartless wheel of life where our childhood caretakers suddenly switch places with us and become the children we once were.

From “Daddy Dreams He Misses the Boat”:

A brass paperweight of that ship

used to anchor his desk. When I ask

where it went, he blinks as if

returning from another

hemisphere into daylight, still

adrift between this continent

and the next.

The concept of travel makes for a particularly prominent, and poignant, aspect of these poems. For context, one need only look at the author’s bio, which informs the reader that Copeland’s parents were missionaries who “stitched continents as if they were linen scraps—America to Asia, Asia to America.” In reconciling the passage from their prime to elderhood, there is solace in remembering her parents as vibrant and mobile, journeying to exotic places (“with my dark-haired mother, a Bible / in his hand and a baby in the crook / of his arm. Three times / he made that voyage”). But this, of course, contrasts with the glaring limitations of body and mind “locked in limbo, between thought and limbic flow.” In the poem “Escape Artist,” the poet remedies this grim disparity by envisioning her father as Houdini, where his errant wanderings become “elopements, as if // he’s running off with a bride / instead of leaving a locked / Alzheimer’s wing / … that sneaky sweet old son of a fox.”

From “Feeding Daddy at 95”:

When I

was small he’d pretend the spoon

was a zooming airplane …

with his bald head and beak-like nose, he’s

a baby bird opening

for a worm as he leans to

meet the airplane bearing applesauce

and ice cream for dessert

Copeland frames old age, dementia, and death in euphemistic metaphor, adapting to the new reality with a kind of magical realism, that special license for indulgence granted to poets. This allows her father, unsteady on his feet in real life, to become a soaring bird, who (in “Falling Lessons: Erasure & Variation”) “swoops, hawk-eyed, / into my watery day / dream of flotsam.” This turns an acrostic of “Alzheimer’s disease” into an alphabetical progression reminiscent of Big Bird teaching us our ABCs, but also mimics the continual diminishment of faculties. For the poet, the gold star earned in grammar school for exemplary work becomes a yellow star taped to her father’s door to “remind the staff he’s a frequent faller.” In “Chicken Dance,” Copeland’s father becomes a befuddled but gleeful child as he “rips paper emblazoned with red / and blue balloons,” unimpressed with the actual gift but transfixed by the dancing rooster on the card. And in “Hymn,” he no longer speaks but “sings his childhood faith,” as children (especially those who grow up to be missionaries) do.

From “Reliquary”:

Her father made a cedar hope chest for her trousseau.

Battered, scarred, now it is mine, a box to hold crazy

quilts, doilies, duvets, the tablecloth Great-Aunt

Gertrude crocheted …

pillowcases dotted with French knots, lazy

daisies, appliqués and featherstitching on white

cotton, linen hand towels …

For Copeland, objects become meaningful, not only as visual/tangible things to hold on to, but to in some way alleviate the pain of “eyeglasses microwaved, car keys stashed in the medicine cabinet, / a cell phone / refrigerated” that accompany the disorientation of old age. The poet chooses instead to clasp on to her father’s gold watch (“the gold warm from his wrist”); rings, found and lost, as tokens of love; and symbols of purity, glamour, and connection to Mother, such as pearls, which show up in various incarnations: “like a pearl behind white clouds,” “pearls scattered, unstrung,” “fallen pearls,” and even an allusion to Steinbeck’s “hour of the pearl.”

In the touching poem “Memory Book,” the poet skillfully and elegantly entwines the alternate realities of past and present into a motif of childhood scenes and themes; one line rich in memory blending into the next line evoking irrevocable loss.

What good’s this stupid book if

I make snow cream for the children

I can’t remember what happened yesterday?

with vanilla, sugar, and milk

Where’s my husband? Did he die? Was it

stirred with spoonfuls of snow.

It is apt that a book of poems about the absence of memory should be crafted so lovingly and honestly by a poet who has such a robust and stalwart one. In the end, there is permission to let go, to let memories of her parents’ well-lived lives console her, leaving the reader to agree with blurbist Roger Weingarten when he writes, “I dare you to walk away from this elegy unmoved.” In keeping with the cadence of childhood, I double dare you.