Joshua Michael Stewart

Joshua Michael Stewart

Break Every String

Hedgerow Books of Levellers Press

ISBN: 978-1-937146-92-4

Reviewer: Ace Boggess

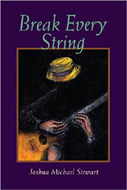

A proper review of Joshua Michael Stewart’s book of poems, Break Every String, should begin not with the poems but with the book itself. The volume is visually stunning, its cover art by Bret Herholz depicting a shadowy guitarist of whom only the hands are visible, along with an instrument and glowing yellow hat. The painting stands out, framed in a wood-stain tint over a plum background. The colors capture the eye and seem to glisten like a new car. This book might leave one afraid to open it out of fear of creasing its spine, adding a scar to what seems otherwise flawless.

Nonetheless, the cover works as an introduction to the writing inside. The music, darkness, and beauty of the painting are present in words as well. Stewart has put together a volume of 52 poems, many of which have appeared in prestigious journals such as Massachusetts Review, Connecticut River Review, Louisville Review, and Naugatuck River Review. They focus on the narrator’s childhood, modern life, and of course, his love for music.

The book begins and ends with music, takes its first breath and dies with it. From the opening poem, “Born in the USA”—about the ins and outs of a troubled childhood set to a subconscious soundtrack of that famous song by Springsteen—to the closing cadence of “Ghost Notes,” this book forms a symphony in five movements. Stewart shows eclectic taste as well, referring at times to heavy metal, jazz, blues, and country-western. He doesn’t just talk about it, though; he lives it, as in this section from “Blues 13”:

We played the blues

badly down in Casey’s

mother’s basement, wrote

songs about working

at the Dairy Queen

and what a drag it was

trying to get laid,

using the “Hoochie

Coochie” riff we lifted

off the Muddy Waters

record we swiped

from the library. The blues,

just another pretty girl

who wouldn’t speak to us.

He feels each note and expresses it in a way that allows the reader to feel it as well, as here in “Heaven in the Devil’s House”:

…Let the room be smothered

in smoky chords and moans

until sun seeps out of the swamp

to halo the cypresses. Let the spirits

of Bessie Smith and Skip James blaze

through windows clouded

by the soot of torch songs to touch

the tired, glistening faces.

Stewart’s way of sharing the feel of the music through his poems will keep his readers awed and grooving. As with all genuine artists, though, sad songs must be written, too. Many of Stewart’s poems are deeply personal, often dark and painful. He deals at times with his aging mother, the death of his brother, troubled life in Ohio, and a grandmother so desperate for another child that she offers a pregnant woman room and board in exchange for the woman’s baby. This happens in “She Called Me Tabitha,” a poem sometimes heartbreaking:

I wanted to write even before I could read.

I’d tell Grandma stories that she’d jot down

on a yellow legal pad to show my mother

when she came to pick me up after work.

What story have you got for me today? Grandma

would ask. Once there was a dead baby…

Aside from music, the narrator’s troubled childhood stands out as a theme in this collection. Stewart discusses his dysfunctional family, early troubles with the law, and growing up in Ohio, a place he doesn’t seem to like—the building blocks that led him to a musical life. Stewart is at his strongest here, delving into the uncertainties of youth and providing details, as he does in “What I Knew, and Didn’t, in the Backseat of My Mother’s Pinto Heading to My Grandfather’s Funeral”:

I wore a tie. I never saw

a real live dead person before.

Would I see the slits in his neck

where they drained his blood?

Do they really sew their mouths

shut? Would he come back

from the dead to tap

on my bedroom window

if I refused to kiss him

at the wake? If I spilled

my Coke on my good clothes

would my mother turn

the car around?

The questions he asks are those most children would think but rarely speak aloud. That gives this sort of poem a connection which resonates, especially with readers that grew up in the Pinto era. Details like that provide instant familiarity and the nostalgia only poetry conjures. For another example, here are a few lines from “Never Ask What’s Under the Bed”:

We move out to the yard, squat down

on five-gallon buckets and scavenge fallen

pears among dandelions and bluegrass,

my favorite AC/DC T-shirt and my woodshop award

stuffed in a cardboard suitcase at my feet.

How easy it is to picture that scene—to be there. A reader is taken back to a place and time with these poems, then grows up with them and moves away.

That brings up the third theme in this book: adulthood. Stewart carefully describes his modern life, too. He shows not only where he’s been, but also where he is now. In “If You Must Ask,” he names all the bleak prophecies his father made for him about mortgages, marriage, children, and the death of his artistic life, to which he responds with defiance: “I haven’t raked a leaf / since 1995.”

With that same defiance, he looks back at his home state in a sequence of poems, all titled “After Ohio,” which are scattered throughout the book. What makes these pieces most interesting is that they begin with letters from his mother or sometimes his brother. It is as if he has sent himself little postcards from the past. After these notes, however, he responds in verse:

…you thumb through a book

of poems because the cover resembles

an old jazz album, and you buy the book,

never the gun, and if someone asks if poetry

has saved your life, you know what to say.

All told, this is an outstanding collection. It deserves to be displayed, read aloud, contemplated, and perhaps sung to whatever music is jamming in the background.