Julie E. Bloemeke

Julie E. Bloemeke

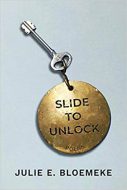

Slide to Unlock

Sibling Rivalry Press

Reviewer: Vivian Wagner

Julie E. Bloemeke’s Slide to Unlock is a collection focused on the powers of technology to connect people and to create distance between them. From phones to cameras to writing itself, the technologies referenced in these poems promise an elusive union, even as they can also, at times, divide. The collection attempts to reconcile the two sides of the technological coin, showing that this paradox is not simply a modern phenomenon, but perhaps a condition of human existence itself.

One of the epigraphs at the beginning of the collection comes from Franz Kafka:

Writing letters is actually an intercourse with ghosts and by no means just with the ghost of the addressee but also with one’s own ghost … One can think about someone far away and one can hold onto someone nearby; everything else is beyond human power … after the postal system the ghosts invented the telegraph, the telephone, the wireless. They will not starve, but we will perish.

Kafka here explores something that interests Bloemeke, as well—the way that technology makes all of us “ghosts.” In letters, phone calls, and telegrams, Kafka suggests, people are not their real, physical selves, but some semblance of those selves, mediated by paper and pen, wire and electricity. Later, digital technologies such as email and mobile phones embody a similar nexus of promise and frustration. Bloemeke’s poems look at that digital divide between people in the modern era, trying to find moments when they’re able, somehow, to cross over, between, and through.

The collection’s first/title poem opens with the dedication/explanation “after the iPhone entry screen, 2007-2016.” As she does throughout this collection, Bloemeke examines here the multiple meanings of words associated with modern technology:

Caught in the present tense,

we are continuously poised

to receive its three-word

command, the insistence

we open with a fall:

Slide.

In this moment, though we are “caught in the present tense,” we hear the echoes of that word, “slide,” reaching, as it does, back in history, to other slides, other falls, that humans have experienced. Once we do as we’re told and slide the phone open, we are

… unaware

of what uninvited

light will bow our heads.

We suddenly find ourselves in another world, lit by its own unique fires, affecting us in ways we can’t imagine or predict. That world, too, is not simply words, but also imagery, color, and pixels that represent the world and detract from it:

We no longer read the words.

A call expects an answer, a dark

screen, a touch.

The sense of connection and disconnection in this poem sets the tone for the rest of the collection—which, not insignificantly, is itself a technological creation, an attempt to communicate, a world that generates its own light.

Many of the collection’s poems also straddle the space between the organic and the inorganic, the human and the technological. In a section entitled “Cellular,” for instance, Bloemeke plays with the multiple meanings of that term—from the cells that make up organic bodies to the cellular phones that are a ubiquitous presence, both in the collection and in our lives as readers. The first poem in this section, “Venice,” focuses on organic cells, but in the context of a collection about technology the language embodies multiple meanings:

Us: wood built from water.

Our cells temporary, vibrant,

winding and dividing

one over the other,

one hand in the other

body pressed to body.

We imagine mitosis.

Cellular division is a way for the poem to consider the act of creation, within a single body and between bodies. The poem’s imagery has technological echoes, speaking of the ways that cellular phones, too, are a way to create, a way to make a world. At the same time, that notion of “division” itself is fraught, signifying a splitting and a limitless abundance.

Another poem in this section, “Electric Mail,” similarly plays with the organic nature of technology’s promise to connect:

Your name presses

from pixels, a promise

of no more silence.

Even as it allows for a kind of cold intimacy, however, that connection is at least partly illusory, given the great distance that such pixels can travel:

We have wires to protect

us now. You are an ocean

away. Still we type, touch

without touch, come closer,

arrive more, and I let you in: my car,

my coat, my sheets. I hold you

in my hand, shocking.

That act of holding another in the form of a phone in one’s hand is something many of us do regularly in this digital era—so much so that our bodies are becoming indistinguishable from our phones. The phone is, perhaps, a body, and vice versa.

The collection ultimately suggests, however, that modern digital technologies are not alone in their creation of distance when we long for intimacy. Rather, our bodies themselves are a kind of technology for keeping what’s inside in and what’s outside out. In an earlier poem in the collection, “Seventeen,” for instance, the speaker describes an actual physical encounter that sounds eerily like the digital encounters described in other poems:

He traces my body

with his hands, as if to create

me, takes joy in seeing the light

empty over me …

In this moment, we understand that the act of touching—whether it’s a phone screen or another person—is an act of creation that’s defined by simultaneous distance and connection. This conundrum of desiring an impossible intimacy is, perhaps, part of the human condition. We can only ever do our best to connect, despite all the various kinds of distance that lie between us.

In a reprisal of the collection’s first poem, the last, “Slide to Unlock: Blue Note,” explores many of the themes raised by the poems that came before, going deeper into the paradox of connection and distance. Here, at the end, the attempted connection takes the form of a letter:

I’ve left you a letter. It is written on blue paper.

This one we will open together, our covers

joined, the spine of us bent to half circle,

releasing all of the loves who could not

love. Watch how they break

the surface, how they begin

their words.

Admit their story too.

This letter is, perhaps, the collection itself, and the book is a technology that attempts to connect with readers. Just as intimacy between people is a difficult endeavor inevitably marked by misunderstanding, so the line of communication between poet and reader always involves some level of risk. Still, the poet suggests, it’s worth a try.