Lynne Thompson

Lynne Thompson

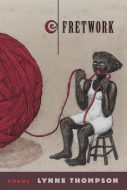

Fretwork

Marsh Hawk Press

Reviewer: Erica Goss

What makes a family – biology, desire, accident or choice? In Lynne Thompson’s Fretwork, family is all of these and more. An adoptee, the author examines adoption’s fraught emotional territory with an unsentimental eye, taking the reader through the web of abandonment, coincidence, and mystery surrounding her origins.

A memoir-in-poetry, the book reverberates with stories of passion and disappointment, always true to its central theme: the puzzle of Thompson’s family. The opening poem, “Composition #1,” confronts the reader with these lines: “If I say the woman who birthed me betrayed me, /you may think that woman badly distilled, needful.”

The detachment implied in the phrase “woman who birthed me” recurs in later poems. In “How the Birth Mother Was Found,” quoted here in full, Thomson’s biological mother is “the laughing woman”:

An old friend heard her laughing—

thought it was me because she’d

heard me before. She turned to

the laughing woman. I went to school

with your daughter. The woman who

birthed me said: I have no daughter.

From these lines it seems that Thompson and her birth mother have led parallel lives, a narrow degree of separation all that kept them apart. An old friend, a laugh; the next step, it appears, must be reunion. But this mother won’t allow it: “I have no daughter.” “Chord,” a villanelle, describes the awkward chill of their not-quite-mother, not-quite-daughter relationship:

Why can’t every choice just be a choice?

Because I didn’t go to her

and why not?—continually—and

even then, I didn’t. What is that?

Whether from cruelty or self-protection, the birth mother’s lack of response echoes throughout the book: she is a cypher, the unwilling object of Thompson’s need to understand. As she writes in “Wombsong,” “You took a gamble, gave me away, and / neither of us will ever know all it cost.”

In “the birth father,” Thompson speculates about her biological father: “he could have been a Holy Roller, // an ocean / a doorbell / a slice of American cheese.” Given the other strange events in her life, the following seems plausible: “unbidden, Siri found him, said: / your father is sitting beside me.”

“Danse Macabre,” a pantoum, dwells on the result of her decision not to look for him: “I’ve been more than complicit / neglecting to seek him out.” If Thompson is complicit, then her accomplice is her birth father – “estrangement our common bond” – as well as her birth mother, who may never have informed him of their child’s existence, a fact Thompson alludes to in “Telling:” “But Beverly, did / you ever tell him about me?”

The complexities of Thompson’s heritage deepen. In “Trace,” she follows the path of her adopted father’s last name: “Of his surname—Thompson—think: former / owner.” That same last name, the name of a slave-owner, is “the name tattooed / upon the African: George Henry Thompson.” This African is Lynne Thompson’s biological great-great grandfather, “stolen from Madagascar, hawked to / Kentucky, run off to Pennsylvania, then on // to Canada….”

Her adoptive father’s story continues in “Genesis” and “The Van Dyck.” An immigrant from the tiny Caribbean nation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, “who came—…coveting America’s ‘normalcy,’” he becomes “history’s onlooker, a witness to how it all dissolves into watery graves.”

The migration continues, from New York to Chicago, then all the way to LA. “In 1930, Daddy Drove to California Without Benefit of ‘The Negro Traveler’s Green Book’” contains lines from the famous Green Book, a guide for African-American travelers in Jim Crow America. In spite of the “risk of a rope” and sundown towns (towns where non-whites had to leave “by sundown”), Thompson’s father makes it to Los Angeles intact. Part II of the poem is a villanelle consisting entirely of lines from the Green Book: “There will be a day— / despite the introduction of this travel guide— // sometime in the near future when it will not / have to be published” (author’s italics). Part III consists of one line: “It was 1966 before The Green Book printed its last.”

Thompson’s adoptive mother, also an immigrant, is “fresh from hibiscus and the Caribbean Sea” (“Bout for Jack & a West Indian Immigrant”). When her mother arrives at Ellis Island in 1920, she has no idea that heavyweight fighter Jack Johnson has just been sentenced to a year in Leavenworth “for loving a whole lot of white women.” Light-skinned herself, Thompson’s mother is innocent of the opinions of those who wonder, “is she a white girl…?” This leads to uncomfortable realizations for Thompson, who doesn’t “want to think about the pale man who had / bedded my Grannie,” a story that returns in the poem “Queens,” where the myths and truths of her heritage collide: “Watch out. Behind the door. / Obeah-man got a secret….” – a secret about the “proper, proper, proper” queens Thompson’s mother claimed to be descended from, a secret that includes coercion, sex, and “the body of a pale Scot minister.”

The mother’s longing for the island where she was born, “rife with sweet fruit,” emerges in the prose poem “Blush.” “Once, in a market, I saw her seek out one ripe mango the way a bride skirmishes for her veil … She let the juice run down her chin and throat and breasts. She did not look at us and, for a time all her own, she sat with hands closed, sticky with pulp.” It’s a display uncharacteristic for a mother so concerned with appearing “proper,” so worried her daughter will become the “unmarried daughter” who “understands less and less” (“Patina”).

Even after death, the mother’s power exerts itself: “I feared she’d return cursing, placing hot embers / on my head where she’s still knocking around… / a crooked thumb still pressed to my throat.”

Poetic forms, in particular the villanelle and pantoum, appear throughout the book. The before-mentioned “Danse Macabre,” a pantoum, tells the story of the poet’s conception, lack of contact with her birth father, and the question of innocence throughout six tightly woven stanzas. In “Lost Spirits,” a villanelle, an eerie story unfolds of an Obeah man (a Caribbean practitioner of the occult) whom Thompson’s father encounters as a young boy, playing alone “up the hill where he was forbidden.” The repeated line, “the Obeah man with one eye, smiling,” builds the tension – the fact that he’s smiling is much more sinister than if he’d been leering or showing his teeth. The final stanza knits together the story’s elements: the boy’s mistake, the narrow escape, the smiling Obeah man that still haunts him:

he just looked at us then winked his left, said

I ran away before anything wicked happened.

Again he laughed but sat so still as he spoke

to us of an Obeah man with one eye, smiling.

Fretwork is a beautifully written and complex book filled with extraordinary language and heartbreaking truths. It offers no easy redemption, heroism, or salvation. Encompassing one family’s migration from the Caribbean Islands to Los Angeles, and many stops between, its power lies in Thompson’s courage and the wry humor of her lines. Discovery awaits the reader on every page of Fretwork.