Matthew E. Henry

Matthew E. Henry

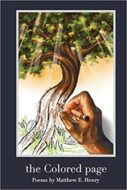

the Colored page

Sundress Publications

Reviewer: Brian Fanelli

Matthew E. Henry’s the Colored page won’t be easy to digest for every reader, especially a white audience. His poems are utterly unflinching and bold in their honesty. He uses “Theme for English B” by Langston Hughes to link together four sections that detail experiences a Black speaker faces primarily within the education system. The opening section begins with elementary school, before the speaker navigates through high school, college, working in a public school, and graduate studies. This is a raw collection that deserves to be read and taught in a classroom. If anything, Henry’s book should strike a nerve and thus spark conversations, if we’re willing to have them.

For those who haven’t read the poem or haven’t read it in a long time, “Theme for English B” details a young Black man’s experience in a college classroom in the 1950s after he’s given an assignment to write one page about himself. The only real guideline is that it must be “true.” The speaker is unsure how to get started, as he questions and interrogates his own identity and the state of race relations in the U.S. The speaker arrives at the conclusion that Black and white aren’t truly separate, but rather, the speaker argues, they’re “part” of the other. The poem does address the professor’s assignment, while widening the lens to contemplate larger societal issues. Henry’s work does much the same. His poems speak directly to everyone from white classmates, to co-workers, to his own students. Each section begins with a line or two from Hughes’ poem. It’s like Henry took the prompt that spawned Hughes’ piece to explore his own identity, while also having a conversation with Hughes’ famed lines and using that to draw from his own lived experience.

Some of the poems come in fits and bursts, strong as a gut punch, while others are slightly longer meditations. In just 11-lines, for instance, the speaker of “my third grade teacher” details a situation in which the lived experience between a Black student and a white teacher is quite, quite different. It reads:

My third grade teacher

explained skin,

the undercurrents

of blood, and how

my face lacked

the ability to bruise

or blush. I tried

to show her a patch

darker than the rest.

she nodded, explained

it was harder to see

on my skin.

Many other teachers like the one referenced above populate Henry’s pages, and many anecdotes herein shine a light on a fairly warped American education system, at least in terms of racial justice. Each of these poems hits hard, one after the other. There’s no reprieve, but these poems aren’t out to make a reader smile or feel good. They cut hard. Henry isn’t afraid to hold back, and I found myself often needing to pause, take a breather, and reflect after every few pages. Many of these poems are individually affecting, and taken as a whole, they function much like a tornado.

In “essay for history B,” another direct reference to Hughes’ poem, the speaker lampoons teachers who expect him to answer every single question about Black history and literature. Even the very idea of Black History Month is called into question here, and perhaps, rightfully so. It opens with the forceful lines, “I’m not a duly elected representative of Niggerdom / who’s authorized to speak for all my people everywhere.” The speaker adds a few lines later, “you see me when convenient.” As an educator, I found this line both painful and striking. It made me question how often I and others may fall into the trap the poem addresses. Do we expect every Black student to answer questions about Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Malcolm X, or Sojourner Truth?

This poem also marks a stark shift from Hughes’ poem. There is a thread of unity or positive acceptance that arrives with the conclusion of “Theme for English B.” That’s not the case here. Instead, Henry’s poem brims with righteous anger, as does the entire collection. Instead of reconciling differences, the speaker concludes, “you do not want to be part of me, or learn from me – younger / and Black and somewhat less free. you should know, the feeling is mutual.” Here we have a speaker willing to make the break, to admit that they’re not going to bond with the teacher or classmates over love of the same music. However, a few lines before the poem’s conclusion, the speaker calls out the teacher for threatening him with docked grades and calling officer Whitman, another reference to American literature. “essay for history B” is another direct reference to Hughes’ poem and quite a challenge to it as well. I’m now thinking about teaching the poems side by side and imagining the conversation that would (hopefully) be evoked among my students.

The latter half of the book details the speaker’s experiences working in the public school system, pushing through a graduate program, and dealing with racism within the literary community, including correspondence with an editor who told Henry to tone down his poems so they’re less offensive. This poem in particular, “an open letter to the poetry editor of [name withheld on advice of counsel]” certainly pushes back against any notion that the literary community is some liberal bastion, totally open-minded. Yet, the poem concludes as defiantly as much of Henry’s work, with the lines, “look, I know what my piece was wearing / when she left the house – she was appropriately dressed / for the occasion and did not need to slip into something / you would find more comfortable. but thanks for the feedback.”

Other poems negate the idea that educators are also racially blind. This is most apparent in the poem “Middle Eastern countries can’t sustain democracies,” a piece that details a social studies teacher’s xenophobic ramblings about the Middle East. Even worse is the fact that the teacher hushes up when a “Brown friend” approaches the table. I’m not so sure one incident described in any of the poems is worse than another, but I found this poem especially stinging and biting, especially its conclusion. Some of these poems, this one included, remind me of those scenes in Get Out, when Rose’s parents pretend to be liberal by praising President Obama. Meanwhile, they literally plan and host a slave auction. There’s a similar level of monstrous hypocrisy that Henry calls out in the latter half of his book. Our liberal institutions are often at fault, too.

Henry’s the Colored page is an important book, one that deserves to find an audience. I sincerely hope that white educators find their way to his work as I believe it will cause them, like me, to reassess their classroom space and the conversations they have with students of color. I’m looking forward to using some of these poems in my own classroom. I hope that their ferocity and the lived experience the poet recounts will engage my students and cause some necessary, if not tough, dialogs.