Marylen Grigas

Marylen Grigas

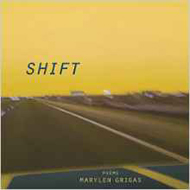

SHIFT

Nature’s Face Publications

Reviewer: Cindy Hochman

“My father of flummox

gave me flummox.”

—Marylen Grigas, “At My Father’s Desk”

Stitch together an expansive mind full of endless questions; a fascination with the scientific deconstruction of cells and art; imagination born of an asthmatic child, with a nod to pediatrician-poet William Carlos Williams; and political commentary hiding in plain sight and wrapped in convivial jollity (in “Concerning the Nature of Inquiry,” we are given “multiple choice: a) bird gripping a gray day, / b) a demagogue’s pursed lips, c) Canada).” Construct a bridge that spans from the mundane to the miraculous, words that shift between lightness and burden with an animated ear for awesome alliteration, on a train from which you study graffiti, and there you have the makings of Marylen Grigas’s powerhouse collection, SHIFT.

Arrival

As if life depends on it, a wobbling first impression

slips from alpha through rays of particles

hunting for its anchor.

Bambi-faced, it asks Are you my mother?

…

Right here! Such a racket a newborn makes

as it stretches, gobbles its fist, searches for sustenance,

reaches for more.

There is a cradle-to-grave quality in the timeline of these poems. From specks and molecules, a child arrives into the world—flummoxed, no doubt—and the birth is heralded as a marvel of lifelong possibilities: science wedded to creativity. There is nothing dour in these poems—oh, except for the fact that they do tend to place a heavy emphasis on uphill climbs, life’s odd swerves, and (let’s be honest here) death and its near-misses. But among the many object lessons learned and imparted by this poet is that, even in poetry, one can attract more flies with honey than vinegar; hence, the tone of a Grigas poem has more in common with Emily Dickinson’s delightful carriage ride to meet one’s Maker than Anne Sexton’s awful rowing. True, the opening poem, “Shift,” can be read as an imperative to get one’s papers in order, but in the interim there are plenty of dirty dishes in the sink, hems to be mended, and so much darned life to be lived, so we need not think about the fact that “lack of time hangs heavy / a thick gold watch on a choke chain.” Besides, the poem ends with “easy easy” (Grigas’s mantra mantra), and in “The Oracle Replies,” the poet tells us to “Soften into your sorrow,” persuasively lulling us, with levity, composure, and her self-described Lithuanian pragmatism. So, why worry?

Foreign Cities

I’ve heard it said that death is a hazy passage

but why not something more definitive, not a loosening

of consciousness, a letting go, shavasana, the dead man’s pose

with shallow breath, cells shutting down their failing businesses,

pulling the blinds, turning the signs to closed, but rather a flash of light

and it’s 1908, long before you were born, when sweating horses

pulled dripping ice carts down dirt streets, grocery carts following

the rag man…

Although, in “Hammocked and Unsprung,” the poet fancies herself “somewhere between lithe / and spry, but neither violin / nor nervous wreck,” there is, of course, plenty to be a nervous wreck about. The “foreign cities” alluded to are not necessarily confined to geography; it is the regions of the body on which the poet’s beloved science, and more specifically, biology, eventually wreaks havoc, and the “failing businesses” encompass the anxiety of personal concerns while hinting at the larger-scale economic ones. But the message here may be that art is the antidote that can push back at the dread that comes with the failing business of aging cells and financial downturns. In “Root,” the poet admits that she wants to “hide behind a word like a wall, / a word that never trembles, panics, never freezes.” In “Ars Poetica,” termites learn that they can “finally and without leadership or direction, / build a nest like a cathedral, / probably to their great surprise.” This is obviously a victory not only for the termites, but for the makers of all things artistic too.

A Hypochondriac’s Guide to the Body

Never mind discussing what is and isn’t postmodern, let’s discuss post nasal, let’s disgust ourselves for the better good of our bodies—minds are another matter. I’ve just read a poem describing the symptoms of someone’s mother. She has faded, but her symptoms remain emblazoned on the back of my esophagus. No amount of coughing helps. Could it be can- can- can’t say it, but chances are good that it is, society riddled with it at every level…

The prose form provides Grigas with the perfect platform from which to use her acerbic but good-natured, and often self-deprecating, raillery and soapbox storytelling to tamp down the unease of living in an uncertain world. Using darkly humorous titles such as “Stanzas with Symptoms” allows the poet to render illness poetically as “the wildfire in my lungs,” giving the reader a nervous chuckle while dampening some harsh and concrete truths. For instance, in “About Muscle,” the poet, in both funny and frightening language, analogizes the human condition to “the sea squirt, a small creature that swims / freely in its youth until it settles on a rock. Then it devours its own brain. / And spinal cord.” Interestingly, this innocuous creature, which seems to bear no resemblance to humans, actually does have something in common with us—a backbone. Perhaps we are being reminded, however subtly, that in order to navigate the process of growing older, we’re going to need one.

Earth: An Introduction to Planet Creation

To the Middle Schooler from aFar More Advanced Planet Who is Running this Experiment: Please tweak my left lung and save Syria. Otherwise, we can’t go on—don’t you see the signs? I’m serious about Syria—unless like many of Earth’s kids your age and much older, you like to see things blow up. Are you taking a wait-and-see attitude?

…

Oh, and here’s a question I’d wish you’d ask your teacher. Please ask why you multiply mass by the speed of light squared. Squared? It’s always seemed arbitrary to me, and no one you’ve created has ever been able to explain it convincingly. In simple language, please. Another thing. Why do I suddenly want to know everything about William Carlos Williams? Everything.

Here again, the poet’s caustic wit attempts to seek solutions for both global and internal disorder. The last line of this poem slyly dovetails into the next poem, “Dear William Carlos Williams,” in which a fragile child muses over the memory of bantam chickens and wheelbarrows “with removable sides” that her grandfather built her, the connection to Dr. Williams jibing with both illness and inventiveness. These literary devices are also poignantly present as the poet lights a candle in memory of her sister, remembers her fireman father injured in a blaze, and her brother refusing Extreme Unction, preferring to lose himself in the TV’s blaring triviality. For Grigas, there is a sanctified suffering in “how pain clarifies, purifies” (“In and Out of the Livery of the Passion”), but the poet is also perceptive to how sound can be used to alleviate this pain—listen closely and you will hear the repetition of “w” (as in whisper) and “s” (as in serenity, solitude, and shhh).

While you were sleeping

Remember the baby’s excited gibberish,

pointing at each picture-book page

then smiling—the way I do

at any happy, hopeful ending?

According to her bio, the poet makes her home in Burlington, Vermont. This is apropos to everything, in light of a chaotic campaign season during which two notable things from Vermont consoled many of us: Bernie Sanders and several pints of Ben & Jerry’s. We all know what happened to Bernie. But thanks to Marylen Grigas’s belief in “happy, hopeful endings,” we can gladly add her poems to the list of things that comfort us.