Ali Black

Ali Black

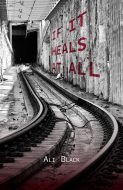

If It Heals at All

Jacar Press

Reviewer: Erica Goss

The cover of Ali Black’s new book of poems shows a train track disappearing into a tunnel. The phrase “if it heals at all” in red capital letters floats against a crumbling concrete wall opposite the track. Taken by Donald Black, Jr., the perspective of the photograph seems poised between arrival and departure. Is a train coming at us, or are we headed toward that lightless place?

If It Heals at All condemns the imbalances in today’s society. Black addresses the emotional and physical tolls of racism, taking us through memories, relationships, illness, and loss. Like its cover image, the book questions assumptions, avoiding any easy answers.

In the collection’s first poem, “Kinsman,” the speaker tries to make sense of the fact that after a baby is “killed / by a gunshot wound to the chest // you still have to ride behind / death’s bloodred breath.” The speaker struggles to understand why the brutal and senseless killing of a baby seems to mean so little, even though she can’t stop thinking about it: “you do not want to face // the red lights, the teddy bear memorials, / the trash, the raggedy strollers….”

And, as if that weren’t enough, she must hear “the radio / scroll through tragedy and woe,” as more heartbreaking stories fill the news. The poem asks us: how can we ever recover? How do we cope with these unthinkable acts of violence?

Black’s poems expose the inequities she experiences every day as an African-American woman. In “As Soon as They Diagnosed Me I Texted My Girl in Atlanta,” she describes receiving a diagnosis of lupus, her friend’s response, and the attitude of the doctor who delivers the news:

She the one who told me lupus was an autoimmune disease …

Dr. Sunshine let the long & boastful term, systemic lupus erythematosus,

settle on his lips like it was a joint he was about to light up

& love. Another Black girl down, I pictured his swirl of smoke saying.

“Bad Nurse” and “Code Yellow” scrutinize the medical establishment’s treatment of people of color. In “Bad Nurse,” the speaker wonders what would happen if “the world started again / without Black women.” If Black women disappeared,

the whole world could start again.

And then, who would die of chronic disease?

And then, who would fill the graves?

And then, what would be the point of doctors?

In “Code Yellow,” Black causes an uproar when she leaves her hospital room in search of “a Polish Boy or a can of peach pop:” “And let’s be honest, if a Black woman keeps waking up to white men in white coats, how long you think she gone lay there before she decides to get up and run?”

The poem captures Black’s awareness of her own vulnerability and the white doctors’ power over her, and the seemingly over-the-top reaction of the hospital when they can’t find her: “The PA system said, a Black female, wearing pink- and maroon-colored pajamas, was missing.”

Black’s poems about her mother’s addiction to smoking illuminate both the disease and the relationship between mother and daughter. “Remembering Smoke” consists of five sections: “I. Morning Cigarette,” “II. Stress,” “III. Secondhand Smoke,” “IV. Quitting,” and “V. Routine.” Her children beg her to stop: “my brother and I exaggerated our coughs like class clowns.” And: “We’d cough and cough and pretend to choke.”

The mother never succeeds in her attempts to quit. “The patch, peppermints, and prayer” seem woefully inadequate against an addiction so powerful that “She did everything with a cigarette dangling between her fingers.” In “Inflammation,” a poem that finds Black and her mother “waiting for another diagnosis,” Black’s reflections move into uncomfortable territory: “If I believed in making up memories to forgive myself, I’d write this poem smooth into a lie.” She frightens her mother—“had her calling me manic,” but “like all Black girls, I was tired of people mistaking my mouth as a disorder.”

Black is adept at writing poems that show how small, everyday moments expose what’s at the heart of a relationships between two people. In “I Am Queen of the Fold,” the speaker observes a woman folding towels at the Laundromat: “She ain’t got nothin’ on my mother. // My mother folded towels like they had somewhere special to be.” “The Ways You Love My Hair” examines her resistance to her partner’s appreciation of her hair, “massive and wild,” the opposite of how she wants it: “You … swat at my hands / as I try to control it.” He loves what she sees as a flaw; she isn’t convinced.

In “The Moments We Would’ve Shared With My Father,” ordinary conversations move from cooking, drinking, and fishing to a much more serious topic: “he’d show you how to // kill a rat with a shovel.” And finally, “Every moment would be // a lesson on / survival.”

Black confronts her anxiety about her appearance in “Bra Log, 2020:”

I have believed

some of what they’ve

taught me about beauty,

and tonight I recognize

that this ain’t about

a bra being too tight.

This is about learning

insecurity is the

worst kind of bruise.

Internalizing society’s messages about beauty leaves its own, deeper scar: “I do not / want to be flawed, which / honestly, is the root of / insecurity.” In this poem, we see how the message that those flaws aren’t beautiful, but instead something to be ashamed of, bury themselves deep within her psyche.

Richly layered with memorable images and phrases, If It Heals at All promotes connection and humanity over prejudice. Ali Black’s poems are an exceptionally accurate account of humanity’s contemporary predicament, as we teeter between our biases and our better natures. By showing us the fear, wonder, desperation, and love she experiences, Black challenges us to confront our shortcomings.