Leonard Gontarek

Leonard Gontarek

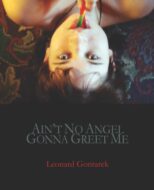

Ain’t No Angel Gonna Greet Me

BlazeVOX [books]

Reviewer: Lee Rossi

You’ll laugh. You’ll cry. Well, maybe not cry—maybe just tear up or breathe a heavy sigh as you page through Leonard Gontarek’s new book, Ain’t No Angel Gonna Greet Me.

Let’s begin at the end, with an interview between Gontarek and poet Jan Starkey. Although we find numerous intriguing and penetrating observations about poetry and the poetry scene, one is also struck by the formal characteristics of this convo. Already on the first page one encounters difficulties and anomalies, almost as if one had just wandered, if not into the Twilight Zone, then definitely into Gertrude Stein territory. Responding to the question, “Language versus narrative poetry, what is the line between them?,” Gontarek replies: “Well, I could certainly describe the line. I think it’s an interesting question just because, um, I’m not sure there, you know, the two, two phases of poetry that are—if you mean language poetry, do you mean language poetry?”

We might as well be in the Rue de Fleurus (Stein’s long-time locus), all that repetition, the halting syntax, the ambiguity and hesitation, the circling around the theme.

Which begs the question: is Leonard Gontarek a L-A-N-G-U-A-G-E poet or a narrative poet? On the basis of this latest volume (his ninth!), the answer, it seems, is Y-E-S.

A giant, economy-size book (over 240 pages), the poetry is divided into three sections: “Carry Me Home,” “Photo of the Poet Holding His Father at Age 3,” and “Fakepath.” The first two, each roughly a hundred pages, are followed by the third, a mere six pages. Why that little bitty section—is it a coda after the two movements of a sonata? Is this as much a musical piece as it is literary? In the interview, Gontarek notes that he plays the drums, while he and his interlocutor cite approvingly Walter Pater’s declaration, “All art aspires to the condition of music.”

There are thematic and stylistic consistencies throughout. In all three sections, one encounters Gontarek the joker and epigrammatist, as well as frequent nods to Buddhism and haiku. In the interview, Gontarek mentions his migration from Catholicism to Zen, and notes that “Zen uses me.”

Part 1, “Carry Me Home,” is a series of short poems (almost haiku), baring a deep sense of insecurity and shame, reworking as in a dream (or a fugue) obsessive themes—a failed relationship, a sense of betrayal. In “Locus,” for instance, the poet announces, “These are my obsessive themes”:

tiny alligators swirling through the plumbing,

falling to my knees & not knowing why,

twin little boy & girl running around a tomb

throwing flowers at one another,

paint flaking for the 17th century, . . .

The Angel sits in the seat next to mine.

She wants to tell me it is a dream.

She moves closer & rests her head on mine.

How seriously are we to take this list? (Is that an allusion to Pynchon’s V. in the first line?) Not as seriously as what we encounter a few pages later, when the poet, addressing a dead or absent lover, confesses:

Can I live without you?

I can live without you for days.

(“Confession,” p. 85)

And on the next page:

The real you, I’ll wager, is in the letters

to the other.

(“Confession,” p. 86)

Part 1 ends in a decrescendo, pain dissolving into numbness. Consider this haiku, its evocation of a crushing emptiness mocking the Buddhist promise of inner peace,:

The pond, level with felt, rust.

Leaves drift down on the surface.

Full mind. Empty heart.

(“Confession,” p. 91)

Even as the pain subsides, numbness prevails: “you don’t cause me pain now / you remind me of pain” (“Confession,” p. 97). Or consider the bleakness of this tiny poem, Part 1’s final gasp:

Pain?

The devil, under his breath,

sneers: fucking tourist.

(“Confession,” p.104)

The pieces in Part 2, “Photo of the Poet Holding His Father at Age 3,” are generally longer and often funnier. “Poem Beginning with a Line by Leonard Gontarek” offers this slice of self-deprecating humor: “People mistake my grouchiness for grouchiness.” Or consider this moment of mockery (from “Running Through The Castle With Gold Scissors”): “In the room the women come and go talking of Frank Langella as Dracula.” Hmm? Gontarek teasing the canon? We also notice, as if to make his point, Gontarek eschewing the rhyme, refusing to please the reader. Or is there a slant rhyme here: Langella / Dracula?

Like many poets, Gontarek has survived the ongoing battles over the indeterminacy of language and come away proud but scarred, determined to make what he can out of his resistant materials. Or as he says in the same poem: “The point of art is to show people, according to one poet, / that life is worth living by showing that it isn’t”—an epigram worthy of any poet’s tombstone. (I’ve already got mine on order.)

At other times, we find a strangely apt mix of imagism and surrealism: “The moon is pudding skin. The ocean is soup.” (from “Local Intervention / written in exile”)

As with Part 1, the materials are various, yet somehow lighter, a bit like bridge mix. Humor rubs shoulders with skepticism, visionary moments with ultimate darkness. Don’t like what you’re tasting, pull something else out of the pile!

“Praying in Darkness / Good Question” offers the following observation: “Because the words sound good together / does not mean they are the truth / or beautiful”. Poor Keats! Grecian urns are down 50 points in high school AP English.

Equally sardonic is this declaration from “Alternate Take”: “I’m not sure if I had / a free pass to Paradise / I would go there all that much.”

Yet there are also moments of tenderness and longing, as in “I Am All Beggar”: “It’s hard / to be in the present / when all the objects in it / are in the past.” Even more than in Part 1, Part 2 displays the splits within Gontarek’s imagination. In “Quit Your Whining and Maybe She’ll Come Back,” for instance, we encounter the dialogic illogic of Berryman’s Dream Songs. “None of it’s fair,” he says to himself, to which himself replies, “No offense, but that don’t mean nada.”

Where does an artist find freedom, that elusive sense of being alive? Gontarek seems to find it in the stylistic restlessness of his poems. Even after eight books, he wants, as Pound exhorted, to “Make It New.” Or as he himself says: “I don’t want to imitate me anymore.”

But of course there are other sources of freedom, sources outside the self. In “Covenant,” for instance, he seems to combine his Buddhism with his love of nature. “There is still a secret,” he tells us, “a boat drifting, decorated with orchids.” I don’t think we have to stretch the metaphor too far to realize that we are all that boat, drifting through life wearing those splashy sweet-smelling garlands. All we have to do is go with the flow.