Nehassaiu deGannes

Nehassaiu deGannes

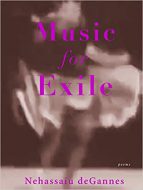

Music for Exile

Tupelo Press

Reviewer: Jessica Drake-Thomas

“It is music for exile … for symptoms of migra/tion. It is the languishing. Pick / through your belongings. Decide what to take,” says the speaker in Nehassaiu deGannes’s collection of poetry, Music for Exile. It’s the easiest thing that you can take with you: music, a gift evident throughout the book.

At times full of lush description, at other times offering a clear lens into two societies by someone who stands a little outside of both, Music for Exile inhabits the space between two homes. On one hand, there is the home in the Caribbean that has been left behind to pursue economic prosperity, and on the other, there is a new home in the United States, where racism is historically and institutionally inherent. Neither place is perfect. There are challenges and dangers in each, as well as things to savor.

The book’s first poem, “Mutter,” brims with references to motherhood (the title itself is a jumbled version of “mother”). The speaker says, “On tabernacle mornings, in the canine hush and rush of trains, I stare / at other women. Pregnant, would I remember to wear socks?” The reader is placed in a busy morning subway station, where the speaker is observing other women. The poem operates as a rumination and is one of the more accessible pieces in the book.

Throughout the poem, socks become a repeated refrain. There is comfort in the idea of a sock, even if the other is missing. “I have lost two children, a hand to marry, some change, a few pair socks. / A gathering of blue hydrangeas. What’s left but a few pair of mismatched socks?” the speaker says. This poem sets the tone for the book, that half of many things is missing. So it is for someone in exile; they have no home, no sense of belonging wherever they are. They are not tethered to the land where they live currently or the land where they lived before.

“Ironweed” focuses on a girl living in Rhode Island after emigrating from the Caribbean. She talks of wearing a cardboard sign for her face, which reads, “HELLO MY NAME IS: MY FATHER’S NAME / IS: IN CASE OF FIRE CALL …” as though she doesn’t wholly belong to herself. Her destiny is not yet her own. She says, “… we begin our thunderous descent. Blood runs. A river runs / down my brown thighs.” Ironweed was a plant used for medicinal purposes by Native Americans for period regulation and pain. Thus, it could be the cure for what ails her. “Yes, menarche shares its name / with moon: this flowering fist is a vain stump of hope.”

The stump, however, refers to the epigraph of the poem, which details the story of Angèlique, a woman who burned down the house of the man who owned and planned to sell her. After she was tortured, then admitted to her action in front of a priest, her hand was cut off before she was executed. There can be no assuaging here. The speaker and Angèlique are each, in their own way, residents of a limbic space, placed in a state of disempowerment and unbelonging by others based on how they look; i.e., their non-whiteness.

In several places throughout the collection, deGannes performs a revisionist sleight of hand, an integration of past and present. Again, in “Ironweed,” DeGannes writes, “Angèlique appears. In a flickering red run / a siren’s angelus, Rhode Island ignites the palingenesis of a name,” in this way resurrecting Angèlique as if she were an avenging angel. Rhode Island becomes the blood-red land of its original Dutch name. The poem concludes: “My bilingual retina hosts her smoldering, my ironic hunger for home,” interweaving the two stories: two women separated by over two centuries but sharing a similar craving for somewhere to call home.

In a later section, there are several music-focused poems that honor various people and their lives. In “My Brother’s Funeral Pallet is an Explosion of Flowers,” the speaker says, “and he burns clean as sandalwood, / and leaves burn green as lizards in the sun,” beginning the poem as if in the middle of her sentence. We do not know what comes before that, although we may be able to guess at the placement of the brother’s body, his being set on fire. “The cancerous cells have sent out their call to hunker down. / Two flamingo-pink ice-cream cones beckon from my hands,” the speaker continues, then pivoting to a memory from years before when the speaker and her brother were younger. The seamless slide from present to past is reminiscent of how a life is presented during a funeral, how years are often compressed into what occurs as a single moment. “When he is smoke, where will he go?” the speaker concludes, releasing the reader from a spell and perhaps releasing the brother’s spirit, the speaker accepting to some degree that all things are impermanent.

deGannes integrates history, music, and vividly personal details to create a book that is alternately devastating and celebratory in tone. There is much loss, particularly when one must leave a home, but there is also joy around the possibility of finding another home, even if this “landing” is a complex and elusive process. deGannes finds music and musicality in the state of exile, when one’s feet are planted in cold soil and one’s heart still resides on the lush island left behind.