Pamela Wax

Pamela Wax

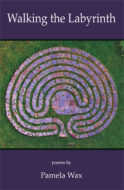

Walking the Labyrinth

Main Street Rag Publishing

Reviewer: Merryn Rutledge

In her elegiac Walking the Labyrinth, author Pamela Wax makes her way through a maze of grief after a brother’s suicide. Wax’s poems reflect a sense of responsibility to find meaning in the mysteries of life and death and to honor lost loved ones. The book’s epigraph by Argentinian poet Antonio Porchia hints at this responsibility as well as another theme: we must maintain connection with our dead, the living, and for Wax, who is a Rabbi, the Divine: “[She] who does not fill [her] world with phantoms remains alone” (author’s brackets).

Wax enters the labyrinth in the opening poem “Howard,” as she asks how and why her brother died: “In what way or manner. / By what means. How did he do it?” Answers are, of course, inadequate to plumb the mystery. In the second part of the poem, Wax uses the suffix “-ward” to express how a loved one’s death causes us to maneuver through the confining spaces of grief: “downward, outward, toward, / eastward, are all in relationship / to” the death. The last two lines of the poem foreshadow a resolution that is also the trajectory of the whole collection: “Seaward, and you begin to smell / salt water long before you arrive.”

The way Wax gestures toward or forward suggests a cluster of motifs she uses in her poems: journeys and navigation, routes and maps. These motifs complement labyrinth imagery. In “Ethical Will,” for instance, the speaker wishes her dead mother could have left her “a roadmap to the promised land” of knowing how to live. She wishes her dead father had left “a treasure map in ink” that would show how to deal with her brother’s death. Wax uses similar imagery in “I keep getting books about character,” a poem that is partially tongue-in-cheek. The speaker wishes she were “equipped for conflict / like a thorough hiker with gear for all contingencies… / slow to anger even when my map / disintegrates in the rain….”

In one of the routes Wax follows in the book, she explores personal responsibility and a desire for repentance that may stem from her not having answered her brother’s last phone call. The theme expresses our natural sense of regret when we realize missed opportunities to have been kinder, more attentive, and more forgiving to loved ones. For example, in “Day of Atonement” the speaker remembers being a child with

… no room

yet for contrition or repentance

in this basket floating down the Nile

toward accountability. I knew

how to say, She did it

of my younger sister, It’s his

fault, of a brother too young

to walk or talk, but not, I’m sorry.

In “M’aidez” (help me), the narrator recalls clues her brother gave for his impending suicide, “Little things / that could have been translated / by a polyglot, but that we wouldn’t decipher” until he was gone. The imagery here exemplifies another set of motifs–codes and secrets–that are analogues, in language, of the hidden turns in a maze. In “My Brother’s Shomer” (guard or keeper), the narrator, Cain, twice admits his guilt as he lovingly prepares to bury his brother Abel. He chants, “He is pure / He is pure / He is pure” as a ritual responsibility and also as though seeking relief from guilt and grief.

Scriptural and Talmudic references, as well as family stories, literary references, and allusions to the history of a people, are woven through the collection. In this way, Wax explores elegiac themes beyond the loss of family members, such as the Hebrews wandering in the wilderness after fleeing Egypt, Jews exiled in multiple Diasporas, and the decimation of Holocaust horrors. She reflects on displacement in “Havahart Live Animal Cage Trap,” a poem that shows Wax’s connections with nature. Describing Russian-American photographer Roman Vishniac’s sensibility in documenting pre-Holocaust shtetl life, the narrator recalls that after he photographed even the tiniest creatures, “he’d always return it to its pond, knowing / himself how it felt to be displaced.” In “I Am Not Descended from Stoics Like Jackie O.,” the narrator links her parents’ grief after President Kennedy’s murder, her father’s grief after he lost his father, and her grandmother’s thoughts of death on the narrator’s bat mitzvah. Wax deepens this pattern of expressing grief by connecting it with her family’s forebears:

… Eastern European Jews,

who ever turned their prayers

towards a Wailing Wall that echoed back

at them, wailing, wailing, because the danger

and despair are everywhere and eternal,

and what else did they know to do.

Poems in the book are ordered to show that as time passes, early grief–raw pain, wailing, and remorse–changes to degrees of acceptance, as in Kubler-Ross’s model of grief phases. Early in the collection, Wax signals her determination to find routes through the valley of the shadow of death to redemptive dreams, dancing, and sailing in waters “open to the winds, / amid parting seas and timbrels” (“Approaching Zeal: a Run-On Abecedarian”). Like the biblical Ruth, Wax eventually welcomes hope, the “Gleanings from the Field” in the poem’s title: “Show me what modicum / of hope lies here on the edges of this field.” The field is a farm field, a field of vision, and a field of energy, as in a gestalt. She celebrates a time of dancing with her brother, quotes Psalms 126:5, and knows the “promise in croci / clawing through snow.”

Among the poems remembering dead loved ones, Wax scatters memories of childhood, encounters with animals, the pleasures of gardening and ministering to her congregation, and humorous reflections on her own personality. These poems circle around main themes concerning the life-death-renewal cycle, the search for paths through difficult experiences, and finding ways to reckon with broken connections and displacement.

While Wax is not a formalist, she shows effective use of form in a sestina, an abecedarian, and in the choices underlying stanzas and lineation. “Day of Atonement,” for example, which is written in tercets, focuses on three siblings and does not resolve the central dilemma of how to atone for thoughtless behavior. Tercets, which tumble onward without resting, effectively match form with function. I also enjoyed instances when the poet-Rabbi’s diction, along with her choice of images and references, was influenced by her life as a Rabbi. In “The Tenth Man,” Wax mentions the Talmudic claim that where ten people gather, the Divine Presence is with them. The tenth man in the poem is the speaker’s absent brother; the poem ends with the sonorous lines: “Altogether, nine stones / sundered from the tenth they seek / for their quorum….” The unusual verb choice “sundered” makes sibilant alliteration with “stones” and “seek.” The repeated “n” sounds vivify the mourner’s moan.

Wax has assembled a fine collection that could have benefited from an attentive editor. There are many prepositional phrases that are misplaced modifiers. A few word choices, such as “sports” a wedding ring in a serious poem about her brother’s lost ring, are small flaws. Finally, for my sensibility, a few poems could have used further sculpting to pare down weighty detail and refine some prosaic language.

That said, Walking the Labyrinth is a marvelous, life-affirming collection. Across oceans and fields of grief and through its complicated labyrinth, Wax moves carefully, lovingly, and reverently to find “redeeming remnants” (“Extinction or Therianthropy”). The end of the final poem is a fitting summation of the journey: “Everywhere, I am growing. Again comes the harvest. / The yield this year abounds boundless.”