Xiao Yue Shan

Xiao Yue Shan

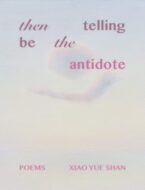

then telling be the antidote

Tupelo Press

Reviewer: Vivian Wagner

Xiao Yue Shan’s poetry collection, then telling be the antidote, is an homage to art as a way of making sense of and transforming the world. The collection explores how creativity and imagination are as necessary to survival in challenging circumstances as food and water—and sometimes more so. Telling can, these poems suggest, serve as an antidote to trauma that might otherwise be overwhelming.

The poems in this collection loosely follow a journey from one home to another, mapping the progress from fragmentation toward some kind of tenuous stability. In this journey, the physical landscapes often embody the emotional ones, and vice versa. In “striations,” for instance, we hear about the landscape mirroring internal emotions: “the long way this land obeys / its shapely waters” reminds the speaker of “how often beauty comes to resemble / surrender.” The speaker also talks about the physical world as embodying what’s in the mind: “I go and return from / the long landscape of knowing.” Like many poems in this collection, this one explores the process of moving and changing along with the land: “this is not the first place we’ve / called here.” The speaker’s experiences cannot, ultimately, be extricated from the landscapes through which they flow.

Similarly, a poem called “rises in the urban population determining that each resident be allotted 1.6 square metres of personal space” concerns itself with the interrelationship between personal space and agency in a family living in a small and crowded space: “we all sat around like we were waiting for someone / to stop by.” At the same time, this family finds meaning despite the cramped quarters, and this meaning comes, at least partly, through language: “we spoke in a language so heavy that we passed / the words around in our hands.” Language becomes, in effect, a possession, and at the same time it creates its own space through its heft and weight.

Poverty—and surviving and escaping it—is a central theme in a number of these poems. In “wealth distribution will not be considered in the economic reform,” for instance, the speaker explores poverty, starting with a moment of almost mythological narrative about the “get rich quick schemes in china” that “always started with two men sitting / on some battered patio.” By the end of the poem, we hear that one man—possibly one of those at the battered patio at the beginning of the poem—says “I’ve got two daughters,” and another one, perhaps the other, “asleep on the table, is silent.” In this moment, even the mythology of poverty begins to break down, as do the people who strive to move beyond it.

The journey in this collection moves through exile and escape toward an attempt to rebuild life in a new place, while trying to bring as much sustenance and hope as possible from the world left behind. Poetry becomes a kind of a raft for traveling from the old place to the new, and also a way of carrying the past into the future. In “the right to work,” for instance, we hear about the “brick stepping-path down middling / through the pacific,” as if that journey were merely a matter of walking down a path, rather than the traumatic process of upheaval and refashioning that we understand it to have been. At the same time, family connections keep surfacing as a way to link the old world with the new. In “inheritance,” for instance, the speaker visits her mother in China, saying “it’s her life, yet I had come, and grown / my hair,” a representation, perhaps, of the growth that has happened since leaving her childhood home, and of the process of returning in such a way that “ruins are rebuilt.”

Food, too, is a connection with the past, and it serves as a way of connecting the past and present. In “kitchen,” we hear that “it takes a lifetime to make a meal,” since the lessons that go into preparing food reach far into the past: “it is as her grandmother has taught her mother.” In fact, food is so important in this process of connecting past and present lives that it can ultimately be conflated with geography itself. In a poem entitled “she says to start with cold water,” the speaker has “crossed the pacific / a great number of times,” but that “now it shrinks in an instant— / in a pot of water,” That the ocean’s vast distance can be seen in a pot of water shows the importance of food and the process of preparing it as a way to understand what the poem calls “a topography of hunger.”

The poems also explore the process of shaping a sense of self in a new place, even as the old place has a constant and undeniable presence. In a series of poems about Montreal, for instance, the speaker seeks to describe a new self emerging from the old. In “montreal II,” the speaker says “I was getting lost all the time so I had to pick up smoking”—with the physical act of smoking integral to claiming a new territory for the displaced self. And in “montreal IV,” a poem in the form of a letter, the speaker says “yesterday I received my passport in the mail. / the photograph is a ghost, but recognizable,” and “I am learning english / from the radio.” Here, there’s a disjunction between the past self and the current one, and a valiant attempt, nonetheless, to bridge that inevitable gap. And finally, in “montreal V,” the speaker says, “I tell the truth in the first half of my life / so I can lie in the last.” The act of telling itself changes, perhaps in order to provide a better antidote to current circumstances, and even if it necessitates some form of lying.

These poems explore what it means to leave a place and make a home in a new one, even as the pieces from one’s old life are fragments that might never fit neatly together. The poems in this collection are ephemeral, with their deliberate lack of capitalization and frequent use of sentence fragments representing the jumbled and sometimes incomprehensible pieces of life. At the same time, the poems have a strong narrative drive, revealing a sense of self-control in their commitment to shaping a life out of traumatic events. There’s also an appreciation of beauty in these poems, as well as an abiding belief that the act of telling is the best—and sometimes perhaps the only—way to make meaning in a shattered world.