Dana Roeser

Dana Roeser

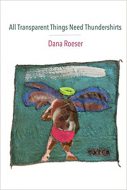

All Transparent Things Need Thundershirts

Two Sylvias Press

Reviewer: Joseph Hutchison

Dana Roeser’s first book won the Juniper Prize from University of Massachusetts Press, and her next two collections won Samuel French Morse Poetry Prizes from Northeastern University Press. This kind of success raises expectations for her fourth collection All Transparent Things Need Thundershirts, winner of the 2019 Two Sylvias Press Wilder Prize. Readers who value poetry with a sense of humaneness and humor will be cheered by Roeser’s latest book.

In All Transparent Things, Roeser applies lyric strategies to stories drawn from everyday life, but these are not conventional narratives. The poet’s version of everydayness is focused more on the mercurial self than the mercurial world. As a result, the stories in her poems are filtered through a shifting sensibility that seems to honor whatever associations come to mind. It is a taste for drift that would be Ashbery-esque if it weren’t balanced by an equal desire for stability. Roeser wants to have it both ways—straightforwardness and obliqueness in equal measure—and the struggle to do so gives her poetry an adventurous improvisational feel, much like John Coltrane playing “My Favorite Things.”

Take the first poem, for example, “Letter to Dr. M.” Suffering from an unnamed eye problem, the speaker is warned by her ophthalmologist to avoid the strenuous exercise of running as it could worsen her condition. The speaker suggests horseback riding as an alternative, which the doctor approves out of an ignorance the speaker finds amusing:

Dear Dr. Maddingly, I’m writing

to let you know I took

seriously your admonition

not to go running for at least

three weeks until whatever the

vitreous jelly stuff that’s

making those gray shadows tree branches

flashing lights in the peripheral

vision of my right eye gets settled. In order

to prevent serious retinal problems

that require surgery. I did the

following alternate exercises:

riding—you did say I could

go riding—my friends and I laughed

at the stable about how you probably

OK’d riding because you don’t

know what it is. Most people

seem to think it’s sitting on a

horse! Ha ha! We love picturing

those people on a horse—or

my favorite—we love picturing

our bosses on horses!

Roeser’s stair-stepped couplets canter on in this way for eight pages, lassoing into the narrative a fearsome incident involving a possible tornado, a visit to her therapist, the death of a friend and (evidently) fellow horseperson, the discovery that shame is her “default setting,” and so on until the poem takes us back to the office of Dr. M., where she remembers or imagines him, the “you” she is addressing:

… with your clock face,

your lovely kind voice and

soft steady hands, peering

into my eyes’ dark depths

with your “ophthalmoscope,” I

just found out it’s called, its

searching magnifying light.

The great virtue of Roeser’s approach is that every turn in the poem feels fresh, surprising, and significant: circularity and openness, humor and seriousness, side by side.

If there is a downside to Roeser’s method, it seems to lie in her desire to force lyricism on language that is fundamentally prosaic. As a rule, this occurs in poems where the lines are shortened to a fault, unhelpfully atomizing the syntax. Take these lines from “Flying Change”:

Sally, our dog,

guarded the

foot

of the stairs.

“Tell your

boyfriend

to be

careful descending

that she

doesn’t

leap at

him.”

And these from “The Fire Academy”:

Where was

it I lived

that there was

a special

fire building

on the

outskirts

of town, off

of some four-lane

semi-main-

drag?

These sentences are plainly prose, and no slicing and dicing will lift them into poetry.

Luckily, Roeser doesn’t often admit prose into her poems, though some of her poetry’s energy comes from flirting with it. She does this throughout the book, but to different effect in different poems.

In the first half of this collection, Roeser’s poems seem to be delivered via her own personal voice, a flirtation with prose as the poet’s life, like all our lives, happens mainly in prose. The flirtation is honest and direct, a side effect of a poet reaching for the meaning in or behind a personal experience, as in “Transparent Things, God-Sixed Hole”:

Once on a sidewalk

beside Erie Street

around the corner

from Underwood

where the pointless

obsolete

tracks run to a dead end

on the other side,

I found a black

and silver rosary …

I kept it

carefully until either

I lost it or it got buried

in the bottom of a purse

abandoned under

my bed or in the

closet. Clutter keeps

me bound to this

earth.

I told Patti last night

that the God-sized

hole in me was

so big and vacant …

The title suggests a gesture toward Vladimir Nabokov’s great short novel Transparent Things, but if it is, the gesture’s significance is obscure.

The book’s second half is a more disparate gathering, both in voice and subject matter. Most of the speakers seem not to be Roeser herself. This becomes especially clear in her extraordinary poem “My Hobby Needed a Hobby,” in which Roeser jettisons the controlling signals of punctuation and presents the longest lines in the book. Yet the language quickly snaps tight like the cabling of a hot-air balloon when it bucks up and hauls the basketed passengers into the blue:

My hobby needed a hobby you know how you get a dog and you have a dog

and then Kurt says we need to get the dog a puppy the dog needs somebody

to play with her to teach and then you have a baby bossy baby needs a little

baby and littler baby and then like you have a thing that you don’t get paid

any money for it’s like an art you do it for the love of it sooner or later

though it gets you know it starts to make you nervous …

The poem’s manic chatter circles out like a planet flying around an invisible sun. It’s an approach that brings to mind A.R. Ammons’s great book-length poem Sphere, though here the speaker is clearly a character, a persona. It’s a terrific performance, the poem’s long lines perfectly reflecting the irrepressible speaker.

Bottom line: at her best, Dana Roeser draws us into her stories with gentle wisecracks, wordplay, flashes of insight, and turns of thought and feeling—making her book a genuine pleasure to read.