Michael Kriesel

Michael Kriesel

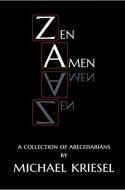

Zen Amen

Pebblebrook Press

Reviewer: Erica Goss

Told in a book-length series of abecedarians, Michael Kriesel’s Zen Amen is a dizzying romp through one man’s investigation of the occult. The abecedarian, a 26-line poetic form that begins with the first (or last) letter of the alphabet and is followed by the next (or previous) letter, is an unexpected yet gratifying choice for poems that include, among others, references to the Bible, H.P. Lovecraft, divination, numerology, chant, crystal balls, tarot cards, and serpent mounds.

Kriesel’s dexterity with the form is impressive in its own right. Virtually all of the poems are decasyllabic (containing ten syllables per line) and half the book is made up of double abecedarians. Kriesel explains the requirements of the double abecedarian in “Notes on Composing These Poems:” “each line’s final letter (or sound) must also follow the pattern,” as in this excerpt from “Night School:”

Zeno lectures in my sleep. “The sun as

you know is a great bowl filled with fiery

exhalations.”

Also in “Notes,” Kriesel shares that with only two exceptions, the poems in Zen Amen appear in the order he wrote them, a fact that permits a rare insight into a poet’s process. Unlike collections where the poems may have been written years apart, yet due to a thematic or emotional connection the poet grouped them together, the poems in Zen Amen appear as Kriesel invented them. This means that the reader encounters the poems in exactly the same order as the poet did. Awareness of this opens an organic path through the book for the reader; insights unfold gradually, and the form’s boundaries recede as the tumble of descriptions and ideas flow from poem to poem in a stream of consciousness that seems completely spontaneous.

Reading this book is at times an exercise in stamina. “Xenogenesis,” “apperception,” “tetragrammaton,” and “zygomancy” are just a few of the recondite terms that appear throughout the poems. Added to the subject matter and the form, this can make for challenging reading. However, these poems are well worth the effort. Their energy is, at least in part, the result of the peculiar pressure abecedarians put words and phrases through, as well as the poet who writes them: every poem needs twenty-six unique words in alphabetical order, for which the poet must range far and wide. This is no easy task—the English language contains plenty of words start with the letters “a,” “s”, “t” and “e,” but far fewer beginning with “q,” “u,” “x” and “z.”

In spite of these restrictions, Kriesel crafted his poems with extraordinary skill, as in the ending lines from “Babble’s Tower,” a double abecedarian:

“We had four-leaf clovers in our backyard!

Extra luck. But during storms, I’d panic,”

you confess. “That’s where lightning’d always stab.”

“Zeus was just jealous of your luck,” I say.

This book is much more, however, than a collection of cleverly-patterned poems. The author’s search for spiritual connection makes for a compelling read. Kriesel’s quest takes him through labyrinths of myriad belief systems, both ancient and modern. From “Middle Pillar:”

Zoroaster started it—good, evil,

Yahweh and the abyss eternally

x-ing swords … Maybe

just in time we could all Jesus ourselves

into what we really mean …

In “New Age,” Kriesel lists some of that particular worldview’s trappings, most borrowed from other, older traditions:

Gargoyle statues. Semi-precious stones. Gnomes.

Healing energy masks no-fault foreplay …

Love is the law, under will.

Meditation group, Mondays, $15 …

Owner wears a “Goddess Inside” T-shirt …

Reiki massages in back. $70.

Kriesel’s explorations through the metaphysical world result in ever-expanding, sometimes uneasy insights. As he ruminates about God, King Midas, zombies, comic-book villains, and his time in the Navy, doors of perception open on questions of authenticity, sexuality, and the author’s lifelong spiritual quest. In “Teen Shaman,” the beginnings of this quest arise in the midst of a bleak adolescence:

Juvenile mystic, I can’t be unique.

Kindred spirits must exist somewhere. Help.

Living in a trailer. Mom works at Photo

Mart. Dad’s gone. I re-create myself in

notebooks.

The poem eloquently summarizes adolescence’s endless, terrible waiting as childhood slowly ends: “Cornfield. Trailer court … / dizzy with my life’s ab- / surdities, freedom still a year away.”

In “Wisconsin Pyramid,” Kriesel comments on the slippery nature of truth, citing the internet, where “The lack of facts doesn’t / hinder speculation:”

Bloggers and websites connect

just about everything from Jesus to

KFC’s secret recipe to the

lost tribes of Israel to the Loch Ness

monster. One popular theory places

Nessie on that grassy knoll in Dallas.

His search for enlightenment, or at the very least, a glimpse into the mysterious workings of the spirit world, results in some truly strange behavior. In “Cup of Air” the speaker barbeques a dead hummingbird, “yanked from air by time and sugar water.” The smoke rising from the unfortunate bird “smells like chicken … permeating the entire / neighborhood, as I invoke the planet / Mercury.” The dead bird receives no sympathy as the poem somersaults through a frenzied ritual, ending with the lines:

Certainly it’s about power, control—

but mostly it’s this reciprocity,

about possessing what possesses me.

In “Eschatology,” that wild energy begins to ebb. With the fatalism that comes with age, the speaker accepts certain realities:

Doomsday makes any afterlife look good.

Coffee. A shower. Soon I’m a stoic.

Back to normal again. Just glad to be

alive and feeling good and here today.

A similar mood infuses “Prince of Trees,” where we read that the speaker has “Been celibate / eleven years. Celibate as trees.” Celibacy “became / habit, which is what a lot of magic / is—new pathways of thought, action.” The manic drive of “Cup of Air” is now spent biking, chanting, cutting wood, and working. “Suddenly I’m forty,” he reflects, the passing years a “card trick done with / these colored leaves, autumn keeps repeating.”

In Zen Amen, Michael Kriesel pushes the abecedarian to its limits, finding within its constraints an apt vehicle for an investigation of the metaphysical realm. Along the way, the poet discovers much more about the world and himself, from the vigor of youth to the wisdom of age. Kriesel’s quest for an understanding that goes beyond the superficial has produced a book packed with powerful images, startling connections, and an oddly endearing eccentricity.