Barbara Hamby

Barbara Hamby

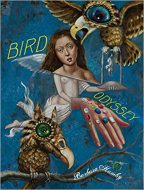

Bird Odyssey

University of Pittsburgh Press

Reviewer: Lee Rossi

Barbara Hamby may be contemporary poetry’s most personable tour guide. In Bird Odyssey, her sixth and latest volume of poetry, she takes us on three separate trips – through Russia, the Deep South, and Classical Greece – all of them informed by her promiscuous learning and enthusiasm for the vagaries of language.

Known as a formalist for her earlier work, these poems are shapely without being overwhelmed by the requirements of form; rhymes abound, but more for sonic pleasure than for enforcing a predetermined scheme.

Variety is the spice that flavors this volume. In addition to personal anecdotes and reflections, we encounter praise poems, prayers, dramatic monologues, dialogues between imagined characters, and even a clutch of sonnets. Humor of a particularly frenetic sort abounds, as in “A Farewell to Shopping”:

Arrivederci, shoes, the lavender silk sandals I bought

in Venice and the dagger-toed love child

of St. Teresa and the Marquis de Sade that made me feel

like a nun/dominatrix in fishnet hose, the loafers

that were too small, but I bought them anyway

and cursed my feet for their toes.

We notice, for instance, a fondness for foreign languages, as well as a zest for elaborate metaphor. We also encounter unexpected bed pals and the casual upending of cliché. This is mannered, possibly mannerist but the mix is consistently engaging.

Given the insistent variety of mode and texture, one might ask: what’s the point? Is there some Grand Central Terminus at which all trips end? In an interview from 2005, Hamby, an Air Force brat, talked about growing up lower-middle-class in places such as Buckroe Beach, VA. Her mother, who figures prominently in her poems, was a born-again Christian, as for a time was Hamby. Her Christian indoctrination left its mark. “The Trinity dies hard,” she says of her predilection for books with three sections.

In this instance, her travels take her through landscapes peopled with the gods and heroes of western culture. After all, she is on an odyssey through Tolstoy territory as well as the Bible Belt and Greece. She approaches these encounters with a tourist’s fascination for the vivid and odd, and a poet’s sympathy for the neglected. In glancing references and asides, as well as in the occasional direct confrontation, she engages the defining texts of these mythic landscapes, and because she finds them wanting, re-imagines them in ways that empower women and other marginalized people.

“Ode to My Gulag,” the first poem in the collection, is a dream poem, filled with sonic fireworks, and ostentatious imagery, including cameos by both Athena and Penelope (who re-appear later in the book). “O inconstant brain,” she asks herself, will the coming day be a reprise of “mud and snow and blood” (Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow) or will it be something better, “will it be spring,” a flowering in which the ideas and shibboleths of the past no longer dominate the present?

Part of the answer lies in the book’s frequent evocation of goddesses, emblems of female empowerment. Some are well-known (Greece’s Athena), others less so. In “Ode to Sirin, The Bird Goddess of the Siberian Milky Way,” she declares, “What woman doesn’t want to be a goddess with wings / to fly over the world of men with their erections / of stone and steel….” What woman, indeed! (No need to comment on the enjambment, or the pun.)

The endpoint of her Russian trip, a Buddhist monastery near Lake Baikal, provides another clue. Consider these lines from “Ode to Luck and All His Roosters and Dogs”:

…all of us creatures

in thrall to our desire for candy, seeds, apples,

kisses, but looking for a way out, too, a dirt road

disappearing in the distance, a path that begins

with one step and then another until we’re in another world,

too much like our own to be our own.

Different, and yet the same. This is wonderfully mysterious, reminiscent of that mystical side of Tolstoy, who wrote: “In life, in true life, there can be nothing better than what is. Wanting something different than what is, is blasphemy.”

Part 2, a journey through the Bible Belt, takes Hamby through more familiar territory, the place where she grew up, and ends again with a heterodox approach to the spiritual life, “New Orleans Dithyramb.” Dithyrambs we are told (by dictionary.com) are songs in praise of Dionysus. This dithyramb, however, is a battle rap between God and Satan, Satan being Christianity’s stand-in for the chthonic energies embodied in Dionysus, one of the lesser, and to my mind, more gender-bending, gods in the Greek pantheon. And, lo and behold, Satan, whose “skin is black upon me,” wins this shouting match, or at least gets the last word, affirming Nature’s divinity:

…I will graze on those leaves of grass like Vishnu’s cattle,

the sacred bovine lowing of mornings laced with bird song

and the wild caw of crows where cars once crawled

like alligators from the swamp of my boiling mind.

I’m fond of details like the nod to Whitman and the mash-up of Hindu gods, crows, cars, and alligators. It’s also noteworthy that while this may not equate with Buddhist transcendence, it does suggest a way of seeing reality that is at the very least pre-Christian.

And speaking of pre-Christian, what about the Homeric Greeks? Part 3 begins with a prayer to Athena. In “Athena Ode” the writer, “adrift in a sea of words,” without direction or sense of purpose, implores the goddess:

…don’t give me away, let me pretend I’m a player

with an ace in the hole, because I know I have nothing,

but sometimes only nothing can open the door to something else.

One might hear an echo of the Buddhist notion “beginner’s mind” (a favorite of Hamby’s) but also an acknowledgement that even a privileged white woman can feel impoverished by her culture.

Her Greek sojourn includes “A Farewell to Shopping” (referenced above) and ends with a group of sonnets which re-tell key episodes in the Odyssey from a woman’s point of view – Nausicaa, Circe, Calypso, etc. Not only do these vignettes upend the canonical story, they foreground the feelings and ambitions of their female characters. In number 6, for instance, “Penelope’s Lament,” we learn that the putative hero’s struggles have been for naught, at least from the heroine’s point of view. Penelope, a female Iago, bares her plans in a stage-whispered aside:

So be my guest, [Ulysses,] finish them off, then I mean

to poison you. O Ithaka is mine. I am queen.

For Penelope, her wandering husband is another unwelcome guest, another unwanted suitor. Once he’s disposed of, she will continue in her role as Queen, the real power in Ithaka. After three thousand years, feminism finally arrives in classical Greece!

Barbara Hamby is a gifted word-slinger, one of the best. But as she herself has said, “witness precedes craft.” For all her playfulness and technical virtuosity, she displays a consistent if diffident earnestness. Unwilling to force her opinions on anyone, she teases and jokes the reader into agreement. Indirect, allusive, elusive, she kids us into seeing our better selves.