Brett Evans and Christopher Shipman

Brett Evans and Christopher Shipman

Keats Is Not the Problem

Lavender Ink

Reviewer: Cindy Hochman

A poem should not mean

But be.

—Archibald MacLeish, “Ars Poetica”

When poems come together in a seemingly disparate fusillade, it is incumbent upon the reader to wade through the maze to get to its core. This joyful and macabre (because in these poems, those two adjectives are not mutually exclusive) collection by Brett Evans and Christopher Shipman should come with an instruction manual for anyone about to embark on the carnival apocalypse that is Keats Is Not the Problem. So here’s some advice to the reader before entering: make sure you read these poems sideways, or on a slant, or upside-down, all along the wavy-watery perimeters, with an open mind and a throw-in-the-kitchen-sink worldview. Breathe in the blissful bonhomie of Evans and Shipman, companions on the same resigned yet beatific wavelength, in the land of Mardi Gras and vampires (vampires which, according to the poets “are all on AARP”). It is well to understand that there is a secret language between them; in fact, this collection is more conspiracy than collaboration, and although things are quite jolly in festive NOLA, many of the lines feel as if they were written from the afterlife by underwater ghosts.

Roach Giant

And after I just see the

are you kidding me? –size

cockroach, somehow not

fleeing the scything foot…

…

I too have started mornings

with kites made of lead

flying off foot, pushing a big

lint racket up the mountain

blowing my own levee…

“Roach Giant” is somehow reminiscent of Walt Whitman’s noiseless patient spider upon the promontory (“surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space / Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them”). For Evans and Shipman, too, even the smallest of creatures become mighty and part of the universe. And the poets’ preoccupation with roaches, given the premonitory theme of this book, does not come out of left field; after all, they say that roaches will survive a nuclear holocaust more readily than humans will.

Reincarnation Therapy

but back home the baby

goes down easy as a window

for watching rain

…

science is an amazing thing

but not

as amazing as us

Even when layered with abstraction, words matter. In most poems, context is everything, but here, the breezy yet grounded tone becomes its own intent and communication. The reader will detect a detailed discipline behind the shabby-chic chaos and casual jive talk—for all the name-dropping, it is not necessary to know who Andy, Jamie, Betsy, or Camille are, as long as we are hip to the sense of community and place that these characters represent. Similarly, the poets’ copious and creative use of the words “kites” and “couches” offers more than just alliteration (“is a couch a sleeping baby / or a sleeping baby a couch”); rather, there is a balance between stay (at home to tend the baby) and fly (at least by virtue of imagination).

Fun and Games

Dear Heavens

we are elastic and mystic

and mucho America

…

it’s end-times tangy

…

& three parting words—

ethanol potbelly pig

It can be said that Evans and Shipman specialize in “end-times tangy,” which later, in “Henrietta Longs for Meaning,” turns to “smashy-crashy fun.” Courtesy of their sleight-of-hand linguistics, the poets keep us delightfully off balance so that we can’t see the oncoming deluge until we’re knee-deep in the muddy swamp. Their excuse? We were too busy celebrating the nuclear winter (and would you like some jazz with that?). Perhaps this explains why the poets admit that sometimes they “do things just to feel flooded.”

Sparkly Blue Shoes

a fully flooded floor

…

a lost balloon

a branchy moon

something

the ghosts fly away with

…

I think I’ll think of a way

to colonize

a new New Orleans

on Mars

Still and all, Shipman and Evans agree that “these poems are terribly fun to write,” as their audience will find them “terribly fun” to read.

Henrietta’s Delicious and Compact Body

and the sky distilled

till an entire species

is at a meaningful party

In the gospel according to John, “in the beginning was the word”—and in the gospel according to Evans and Shipman, the word was … meaningful. The reader will wish they had a dollar for every time the word “meaningful” is mentioned; there is even a whole chapter called “Meaningful Poems,” and there must be something meaningful in that. In “Nola Still Life no. 2,” “money’s a meaningful mouth.” In “The Gumbo Party” (did you notice that there’s a lot of partying going on down there?), “the monster-pump noise was more / meaningful than the smell / and someone would say something / meaningful afterward.” A fist is meaningful in “Henrietta Longs for Meaning,” but, alas, not everything is meaningful; by the time they get to “Making Believe,” the poets concede that “all I learned is / meaningless.”

Keats Is Not the Problem

maybe my gifts are best given

in another world

where we ain’t afraid

of no ghosts …

…

Keats is not the problem

something meaningful happens

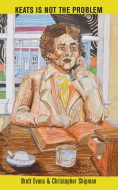

A colorful, somewhat comical-looking Keats, illustrating the shared camaraderie of the poet, complete with literary accoutrements (book, water, ashtray, and of course, pill drawer), adorns the cover of this book. Keeping in mind that Keats succumbed to tuberculosis at age 25, we can surmise that for Brett Evans and Christopher Shipman, he becomes the synecdoche for early death that only poets can find romantic.

But Keats is not the problem. There are no problems. Everything is cool and dandy, so let’s have a party before we’re swept up in the carnage. As the poets raucously proclaim in “Marianne Moore’s Cherry Apocalypse”: “We’re selling art here!”

Now what was the question?