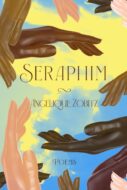

Seraphim

Seraphim

Angelique Zobitz

CavanKerry Press

Reviewer: Brian Fanelli

Angelique Zobtiz’s collection Seraphim is bold and fierce. It contains a multitude of voices, including Greek Gods and various other deities, and it references prominent Black women, including bell hooks, Megan Thee Stallion, and Whitney Houston, to name a few. Zobitz has a knack for blending high and low brow cultures and crafting poems that address everything from personal history to sexuality, race, and power. The collection feels like a raised fist, ready to puncture and protest various systems of oppression.

Zobitz has a unique way of rewriting famous biblical stories to put a personal spin on them, all while creating distinct voices in her poems. For instance, in “Angelique, an Origin Story,” she rewrites the story of Mary and the virgin birth, or, at the very least, references it to address a broader theme of identity and motherhood. The poem also pushes back against the very notion of the virgin birth with its opening lines, “My mama said, I was blessed born. Said, she didn’t need divine / messenger to convince her of what she carries, knew immediately // that I didn’t need to be brought into this world by virgin or conceived // as sacrifice.”

Furthermore, in this piece, as much attention is placed on the mother as the child. The mother gets a lot of credit not only for the birthing process, but also for surviving prior to that. That’s most evident in the poem’s closing lines: “My mama said when they laid me to her breast, she cradled me to her / chest where her beating heart hummed of survival and salvation, and // that throbbing tune lulled us both to sleep. My mama said, a punk // girl can dream of angels and know when one manifests. / She said she looked into an angel’s eyes and claimed it as her own.” This last line is especially interesting as the daughter takes the place of Gabriel as the angel. This poem sets the tone for much of what’s to follow, giving a ferocious and often female voice to familiar biblical and mythological stories.

Much of Seraphim also pushes against white supremacist constructs. “Kink Therapy, or An Alternative History of the World” upends racial power dynamics. In it, a Brown female speaker mentions sliding a noose around the necks of White men, while putting her boots on their backs. She calls them “miserable beasts” who she made into “collared horses” that carried her burdens, while her heels dug into their flesh. Yes, it’s a raunchy poem rooted in BDSM lingo, but it’s memorable for the way it challenges conventional structures. In the last two stanzas, the speaker mentions her favorite “client,” one who offered a “sweet thank you for every bruise.” He also begged her to “beat his guilt away, to be tethered to a table, the Saint Andrew’s cross, or the ceiling.” One of the lines near the poem’s conclusion, “He / sought absolution and I spoke reparations” drives at the heart of the inverted power play that the poem explores. It’s also another example of how unabashed the voice is in this collection.

Also of note is the way Zobitz addresses sexuality, even in religious spaces, as well as some of the hypocrisy that surrounds it. This is especially true of “If you’ve ever visited a Pentecostal tent revival, then you know.” The poem begins with the image of a “young, sanctified girl” rocking “an Anita Baker hairstyle.” She aims to impress the pastor’s wife so she’ll find her suitable for her son. Yet, this also draws a reaction from other churchgoers, who whisper about her and view her as a temptress or the Devil, the typical negative associations given to women throughout history, or in the case of Christianity, hearkening back to Eve and the fall of Eden.

Yet, the speaker questions if the gossip and anger from the elderly churchgoers, the women especially, stem from the fact that they miss being that young and finding pleasure in sex. Zobitz rewrites the image of the temptress and casts this girl as someone who can save the man. The poem concludes with the strong last lines, “All of them wishing and / forgetting he was waiting for a moment to be let free / and saved by someone who was braver than judgment / so he could be baptized into new.” Here, the girl becomes salvation, not damnation.

Zobitz also frequently references the Greek gods, placing them in contemporary settings, or using them as a simple reference point. This is notably apparent in “After Listening to Alicia Keys’ ‘When You Really Love Someone.’” Here, the speaker pines for an “uncomplicated man,” one who would do anything to have her. She wants her “own Hades,” a man as “cool and fresh as autumn air.” Yet, she then transitions into more modern imagery, as the speaker mentions a “gray sweatpants man.” Like some of the other poems, the piece explores themes of pain, sadism, and BDSM, too, unafraid to address some of the more deviant sides of sexuality. Along with that though, there’s also a longing for love, worship, and affection. This is especially true in the poem’s second half.

I crave silkily delivered threads, toothmarks to the throat.

Tying me down electrifies my spine and tingles my toes.

I need the intensity of a lover’s attention—a

Hades man’s assurances he’s thinking of me.

I love the night for its hidden possibilities.

I want to be a worship altar inside someone’s home,

draped in desires, token of affections, talismans.

A treasure cradled on the lap he’s made a throne.

He holding my hand through heaven and hell.

He the smell of fire during the frost inside

my nose, tangled in my hair and sucking at my ear.

A Hades man, whispering for me to come

back to him soon.

Seraphim is a sharp, well-crafted collection, rooted in religious mythology to address much broader issues of identity, race, and sexuality. Zobitz is ferocious, a distinct poet with much to say.