Diane Seuss

Diane Seuss

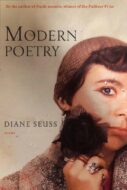

Modern Poetry

Graywolf Press, 2024

Reviewer: Erica Goss

A testimonial to Diane Seuss’s enduring commitment to the art of poetry, her latest collection is harrowing, hilarious, disconcerting, and fearless. This memoir-in-verse reverberates with pitch-perfect observations gleaned from her years as an academic outsider, the combination of pain and pride forged during her working-class upbringing, and her psychic connection with quintessential Romantic poet John Keats, himself an outsider artist in a deeply class-conscious world.

The book’s cover shows a photograph of the poet as a young woman. Sprinkled with bits of debris, it underscores the shaky balance between beauty and brutality Seuss confronts in these poems, the constant adapting and readjusting that occur over a life in the arts, and the costs of devoting oneself to that art. Throughout the book, Seuss evaluates the results of this commitment, asking and answering questions of worth and accomplishment, and whether these are actually the appropriate criteria for measuring success.

“My Education” pulses with details of a hardscrabble, working-class life, where the effects of poverty and food insecurity were part of everyday existence. As much as these experiences have influenced her outlook, however, Suess is determined to keep them neutral:

Not just what I feel but what I know

and how I know it, my unscholarliness,

my rawness, all rise out of the cobbled

landscape I was born to. Those of you

raised similarly, I want to say: this is not

a detriment and it is not a benefit.

The word “cobbled,” a reference to resourcefulness born of need, appears throughout the poem: “cobbled house,” “meals were cobbled,” “the cobbled lushness of the trees,” as well as scenes from rural poverty: “shotgun pellets / in the rabbit meat,” “graves scattered / like chicken feed.” Tension arises between the privations of the world Seuss describes and the sensitive, intelligent girl growing up in it: “I loved / books but learned very little in school.” She tunes out her surroundings, “something I could do / inside my head that muffled the teacher’s voice / like she was speaking into a canning jar.”

“When I needed Keats, I got him,” she writes later in the poem, absorbing lessons from him and Joseph Conrad, all in service to the constant activity she calls “my project:” “My project / was my life.” This project, originating from a thirst for knowledge, had “no vision or overarching / plan. There was only foraging for supplies, / many of which were full of worms or covered / in dust, like apples on the orchard floor, / and furniture junked on the side of the road.” Suess builds a world from these discards, finding value in what others have abandoned; as she writes near the end of the poem, “A cobbled mind is not fatal.”

“Modern Poetry,” the collection’s title poem, opens:

It was what I’d been waiting for my whole life,

but I wasn’t ready for poetry. I didn’t have

the tools.

These lines establish Seuss’s calling as a poet while acknowledging her struggle to absorb the work of poets appearing in the Modern Poetry textbook: Roethke, Stevens, Hopkins, Williams—and then, Sylvia Plath, the “final modern poet” in the book, whose life Seuss summarizes in a curt, sped-up biography: “smart, angry, angry at men … depressed, cheated / on, dead.” An emotional connection occurs between the eighteen-year-old Seuss and the poems of the deceased Plath: “I wanted to love Sylvia, but to love her would mean / loving someone who would have hated me.”

“Modern Poetry” exposes an educational system designed to take things at face value. In her early days at college, Seuss gets As by “faking it” and “maybe / because the professor felt sorry for me, and I’m not / just saying that.” On the surface, the young Seuss appears to be doing well, but she knows better: after looking up “charlatan” in the dictionary, she recognizes an uncomfortably familiar quality about herself: “A quack, which yes, I was /… Who isn’t a quack at eighteen?”

The phantom presence of Keats, who died from tuberculosis at age twenty-five and therefore remains forever young in our collective memory, is scattered throughout the book. “All activities of the mind now seem quaint, / like dolls with lace faces unearthed / from beneath the attic stairway,” Seuss writes in “An Aria.” “Now, to unmuffle myself, I read Keats’s love letters.” In “Poetry,” she considers Keats’s often-quoted phrase from “Ode on a Grecian Urn:”

Maybe Keats was preternaturally

wise, but what he gave us

was beauty, whatever that is,

and truth, synonymous, he wrote,

with beauty, and not the same

as wisdom.

The poem explores various interpretations of Keats’s assertion, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Does beauty exist in isolation, or is it merely an equivalence? Suess writes, “it is not something to work on / but a biproduct, at times, / of the process of our making.”

In “Romantic Poetry,” Seuss considers Keats as an individual separate from his poetry. Here she ponders the trajectory of his life, and how she and he are linked, blood to blood: “my blood / and cast-off ovulations” connect with “the droplets of arterial blood” whose color Keats understood to be “his death warrant.” She kisses his death mask, “until the plaster warmed,” after which “my lips were blossom-white, / my face, chalked. Like I’d caught / something from him, / and I don’t just mean consumption.”

Speculation regarding Keats’s afterlife continues in “High Romance.” Now that Keats is a ghost, love and poetry—the two elements that determined his life’s directions so completely—matter less. The love he once felt for Fanny Brawne has died down: “It was diffuse, like an atomized / perfume, or stars as the poor see them, / who cannot afford glasses.” He and Fanny are now just “concepts,” as Seuss puts it: “they each inhabited the same amount / of space, like a tablespoon of butter and a tablespoon of lard.”

“You would not have loved him / … He brushed his teeth, / if at all, with salt./ … His pits / reeked, as did his deathbed.” These lines from the ironically-titled “Romantic Poet” recall the well-meaning, or not-so-well-meaning, advice we receive from those expressing concern and puzzlement about our passions and obsessions. We remember Keats for his sublime poetry despite his indifference to personal hygiene, a fact Seuss emphasizes with the last line of the poem: “But the nightingale, I said,” which is also the book’s last line.

That one line stands up to the criticism, apathy, and hostility a lifetime commitment to the arts invites from much of the general public. “Romantic Poetry” establishes an ultimatum: either you understand the nightingale’s significance or you don’t. This revelation encompasses Seuss’s thesis: being a poet is an extraordinarily difficult choice, but the rewards—even those understood only by a small, dedicated group, a group for whom the textbook Modern Poetry opened worlds of possibility—are worth it, even if it takes a lifetime to express oneself the way those poets did.